Adelaide: Restricted Development

Map by Nathan Etherington.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

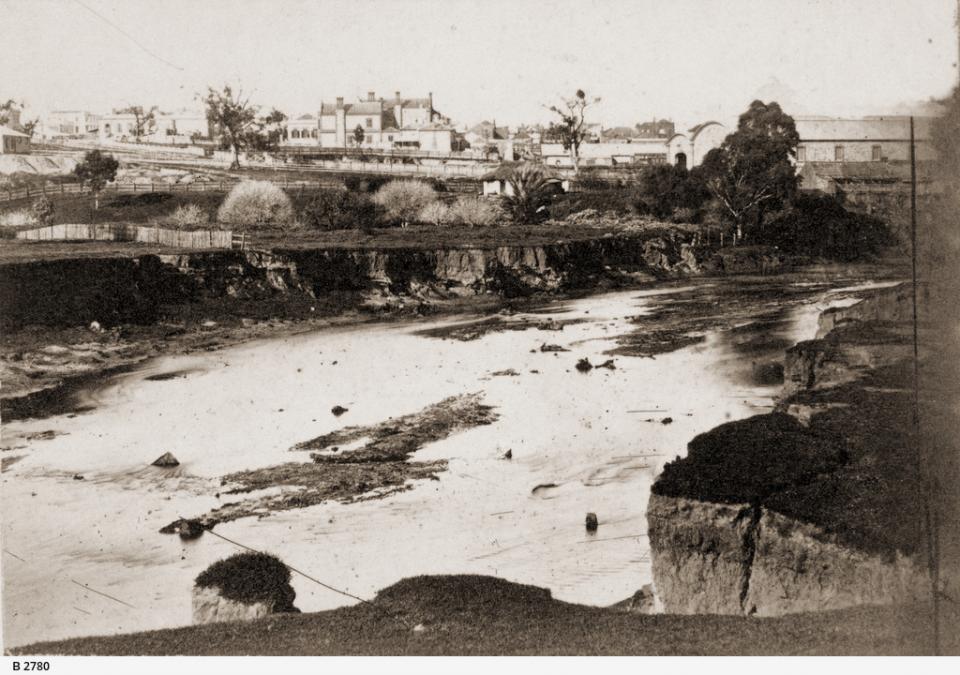

Adelaide is located between the sea to the west and a low range of hills and desert to the north and east. It has a Mediterranean climate of light winter rains and hot dry summers that average 27–29˚C (maximum 46.1˚C). The city receives an average annual rainfall of 550 mm per year. Water scarcity has been an issue ever since it was founded by British settlers in 1836. In late summer, after several weeks of high temperatures and little rain, dust storms (and, in many years, bush fires) frequently visit the fringes of the city.

Planned around a central business district, ringed by open parkland and surrounded by suburban lands, Adelaide’s location was determined by a freshwater stream, called Karrawirra Parri by the local Kaurna people and the River Torrens by settlers. The river was, in fact, a string of water holes that drained into swampy reed beds near the coast and ceased flowing each summer.

Despite the lack of a substantial and continuous source of fresh water, the population grew steadily, regularly putting efforts to improve water supply infrastructure to the test. The first reservoir was not properly completed until 1862—a small affair drawing water from the original string of water holes about 15 kilometers upstream from the city.

The need for a reliable supply saw five more reservoirs built by 1903, serving a population of around 200,000 people. But even these reservoirs were relatively shallow and struggled to guarantee the water supply in periods of drought.

For the past 150 years the story of Adelaide’s water supply has been one of periodic inadequacy, either in quantity or quality. In recurrent periods of drought, compulsory restrictions on demand have been imposed to conserve supply and “manage” shortfalls. “Waterproofing Adelaide,” the name of a 2005 government-commissioned report, has been a constant but elusive goal for the citizens of the city for almost 200 years.

River Torrens, looking east. Unknown photographer, ca. 1860.

River Torrens, looking east. Unknown photographer, ca. 1860.

Photo courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, B-2780.

Accessed on 13 March 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

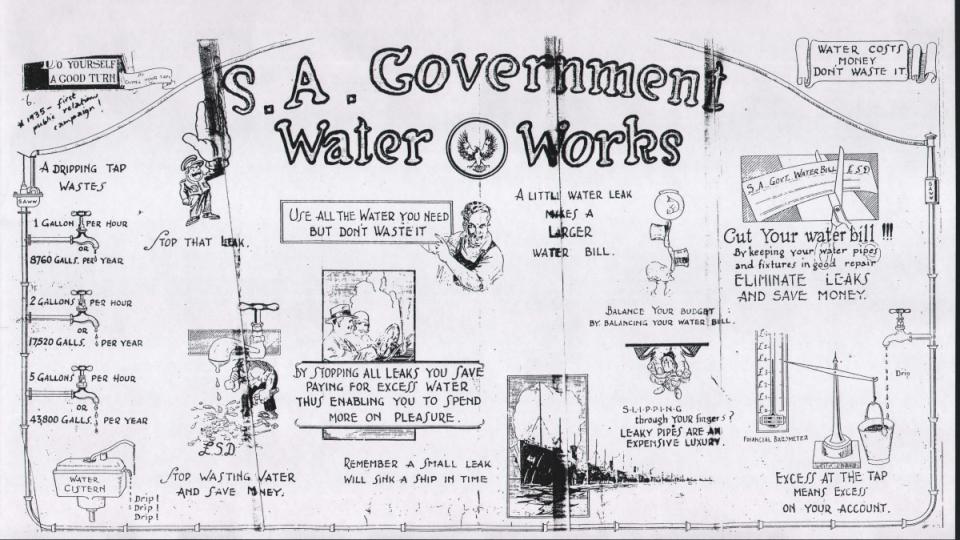

1927–29; 1930–31, and 1934: Water Restrictions and Inadequate Storage

There had been significant droughts and periods of restricted water consumption before the 1920s. In 1914–15, for example, the price of water was increased sharply and the use of any reservoir water for gardens was prohibited. Officers from the Water Supply Department issued special warnings to racing, lawn bowls, tennis, and golf clubs to restrict their water use. But the restrictions from 1927 to 1929 and again in the early 1930s raised the level of alarm, with concerns of epidemic disease should the shortage prove catastrophic.

The city’s then-largest reservoir, Millbrook, virtually ran dry in the autumn of 1929 and Adelaideans were shocked that its level had reached the “lowest witnessed since catchment was constructed.” A township that included a Methodist church and post office, which had been sacrificed to make way for the reservoir, began to reappear as the water receded. Information about the amount of water available in storage and the amount consumed was regularly published in the papers.

Old Millbrook Bridge, usually underwater, exposed by drought. Unknown photographer, c. 1930–34.

Old Millbrook Bridge, usually underwater, exposed by drought. Unknown photographer, c. 1930–34.

Photo courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, B 6477.

Accessed on 13 March 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

At this time not every house had a water meter, and the authorities increased their efforts to increase the number of metered premises. In addition to restrictions on water use, the low water pressure meant that in some suburbs water was barely supplied. Firemen complained of the difficulties caused by low water pressure. By 1931 the Engineer for Water Supply declared Adelaide was “sitting on a volcano” and must “impound new water” by constructing a new reservoir to safeguard the city. By 1938, the state’s largest reservoir, Mount Bold, was complete. Located southeast of the city it holds enough water to supply the entire state for only 79 days if used in isolation.

In 1935, South Australia’s Water Works Department began its first public water conservation campaign. Unknown illustrator, 1935.

In 1935, South Australia’s Water Works Department began its first public water conservation campaign. Unknown illustrator, 1935.

© SA Water.

Photo SAWater library 259954 (First water conservation campaign poster 1935) courtesy of SA Water Library.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

1947–1955: False Hopes of a Permanent Solution

Water shortages loomed large again in the late 1940s and early 1950s, with zoning of water restrictions used to spread the burden. Hand watering of gardens only was permitted, and newspaper editorials bemoaned user selfishness and the lack of foresight of previous governments. Reports suggested a number of buildings burnt down “owing to lack of water.” During one shortage the news reported that a local mother was forced to wash her baby in water from the ice-chest drip-tray.

The long-held dream of accessing water from the River Murray (approximately 60 kilometers from the city) was now both urgent and also feasible. The plan was to pump the river’s water into the city’s shallow water storages to provide enough water for the growing population. The Engineer-in-Chief assured citizens that once the pipeline was completed, Adelaide would never again endure a water shortage.

Mild steel concrete-lined pipe leaving E&WS yard in Kent Town as work on Mannum-Adelaide pipeline begins, 1951. Unknown photographer, 1951.

Mild steel concrete-lined pipe leaving E&WS yard in Kent Town as work on Mannum-Adelaide pipeline begins, 1951. Unknown photographer, 1951.

© SA Water.

Photo Book011pg018image045 (Mannum-Adelaide pipeline, first pipe leaving Kent Town waterworks yard, 1951) courtesy of SA Water.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In 1955 the River Murray water began to supplement Adelaide’s supply, ending five years of summer water restrictions across the city. Water carried by the pipeline did alleviate water shortages for several decades, although it didn’t ensure all suburbs received good water pressure. The quality of Adelaide’s “hard” water was notorious (it was common folklore that the only two cities in the world where cruising passenger ships refused to take on water were Aden in the Middle East and Adelaide).

Water scarcity did see local innovations, the most famous perhaps being the commercial production of a dual flush toilet. This invention, installed in new homes from 1981, aimed to reduce the wasteful use of potable water. In the early 1990s, full cost-recovery pricing, as part of a nationwide push toward water market reform, also reduced the growth in demand. Nonetheless, the perception that Adelaide’s supply was underpinned by the Murray remained. This ensured that long-established attitudes towards European-style gardens, and later household swimming pools, were not seriously questioned. Backyard rainwater tanks, although still in evidence in older homes, were regarded as relics of a drier age.

2003–2011: Permanent Restrictions and a New Technological Solution

Australia’s Millennium Drought began in 1996 and lasted over a decade. The nationwide drought threatened the sustainability of the whole Murray-Darling river system, and with it the future of dependent rural and urban communities. Adelaide’s water supply, “underpinned” by the river since 1955, was no longer guaranteed.

In July 2003, water restrictions were imposed for the first time since the 1950s. Initially the restrictions covered the timing, duration, method, and frequency of watering gardens and grounds. Cars were to be washed only by bucketed water. Filling swimming pools was restricted. These “Level 2” restrictions became “Permanent Water Conservation Measures” in October of that year.

In January 2007 more restrictions, again limiting the time, frequency and methods of watering were imposed. Restrictions were increased eight more times until finally being revoked towards the end of 2010. The 2003 restrictions, however, were made permanent and are now known as “Water Wise Measures.”

In addition to restricting water use, rebate schemes were offered for the installation of rainwater tanks, greywater systems, and water-saving plumbing fittings. In 2006 the building regulations were amended to mandate supplementary water supplies in all new dwellings. By 2007 over 40 percent of dwellings in Adelaide had a rainwater tank, more than double any other Australian capital.

The Millennium Drought’s impact was felt across the nation. Competition for River Murray water increased inter-state tensions, especially when in October 2007 the Adelaide Advertiser reported that “emergency plans had been prepared to supply Adelaideans with bottled spring water for drinking.” While this never eventuated, when the drought broke in 2010 Adelaide residents had lost their complacency regarding the city’s water supply. The drought’s legacies include a desalination plant capable of delivering 50 percent of Adelaide’s water annually, permanent water saving measures, regulations encouraging household water tanks, infrastructure projects to capture stormwater, and an ongoing public interest in the management of the Murray-Darling Basin.

The Millennium Drought prompted South Australia to secure alternative water supplies. Adelaide’s Desalination Plant was commissioned in 2011. Photograph by SA Water, 2011.

The Millennium Drought prompted South Australia to secure alternative water supplies. Adelaide’s Desalination Plant was commissioned in 2011. Photograph by SA Water, 2011.

© SA Water.

Photo Desalination 028a (Adelaide Desalination Plant 2015) courtesy of SA Water Library.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The lack of an adequate water supply has been a constraint to Adelaide’s development since its inception. Local infrastructure developments, responding to political and engineering imperatives and with little or no consideration of environmental equilibrium, regularly failed to keep up with demand. Seeking supply solutions from further afield merely deferred the environmental problems for several decades. The city remains vulnerable, affected not only by local climate and weather patterns, but by water consumption decisions beyond its jurisdiction. While recent efforts to diversify water sources and reduce demand may add a level of temporary resilience to Adelaide’s water supply, history suggests there will be more challenges in the future.