Perth: Water Beneath the City

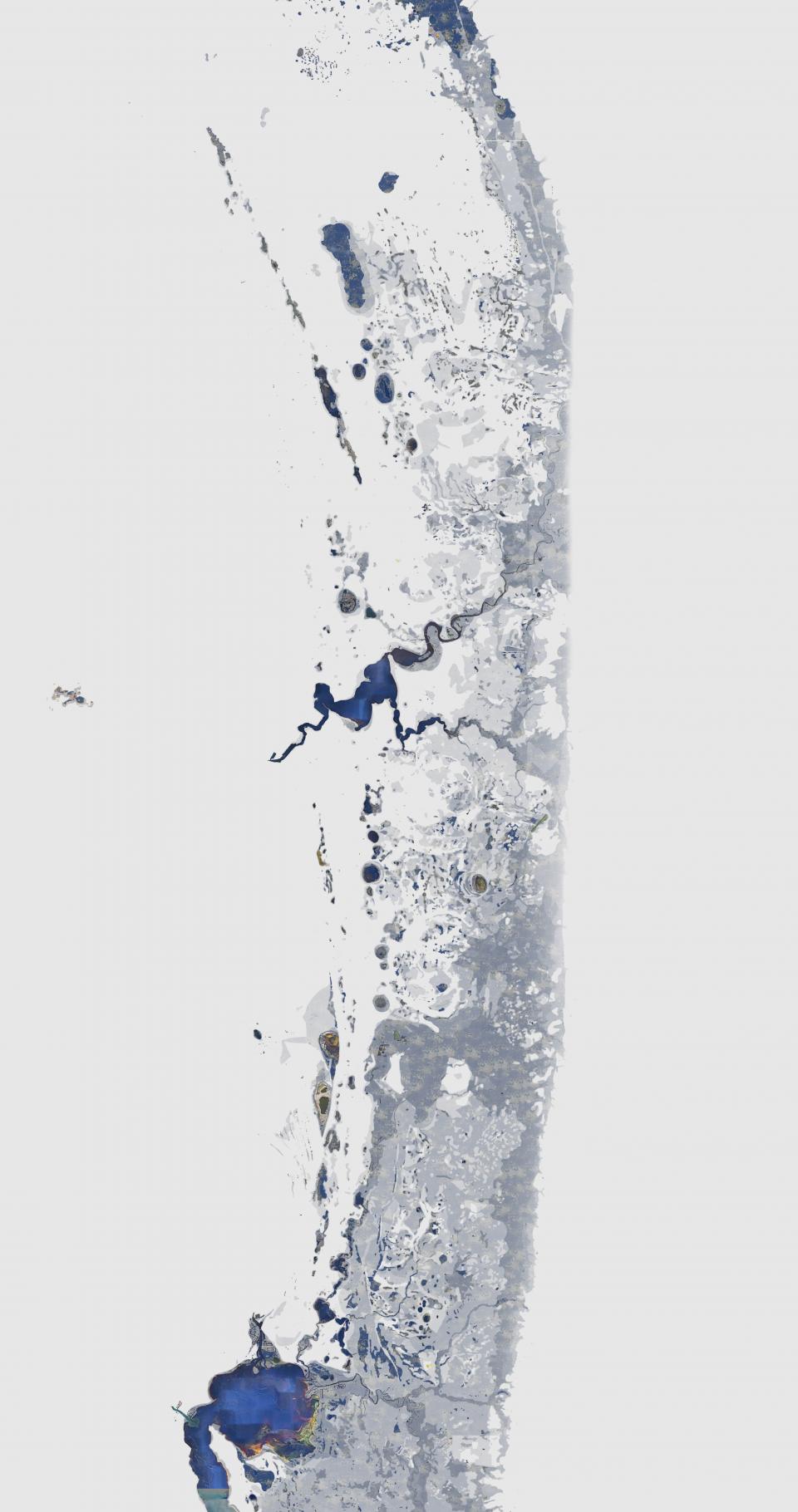

Map by Nathan Etherington.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Perth is the only capital city in Australia to rely heavily on groundwater for its water supplies. Founded in 1829 as a British colony on the west coast of the continent, the settlement at Perth grew to sprawl across the Nyoongar lands of the Swan Coastal Plain. The early years were difficult for colonists who arrived unprepared for the long, dry, and hot summers of the site’s Mediterranean climate. For most of the nineteenth century, the people of Perth relied on natural springs and household wells for their water supplies. Their proximity to cesspits meant that drinking water was often contaminated and diseases spread easily. The association of nearby wetlands with disease, as well as demands for fertile land and flood management, prompted a series of drainage programs that transformed the hydrology of the Swan Coastal Plain.

For thousands of years, Nyoongar had followed the chain of wetlands along the coast, caring for their country while collecting food and other resources. These wetlands were fed from the aquifers of a vast groundwater system that lies beneath Perth’s sandy soils. Near the surface are large reservoirs of water, the Gnangara Mound to the north of the Swan River, and the Jandakot Mound in the south. Beneath these are deeper aquifers: the Leederville Aquifer, and lower still, the Yarragadee Aquifer, which lies beneath the entire Swan Coastal Plain and holds almost 2,000 times as much water as Sydney Harbour. The vast reserves of the Yarragadee are thought to be up to 40,000 years old.

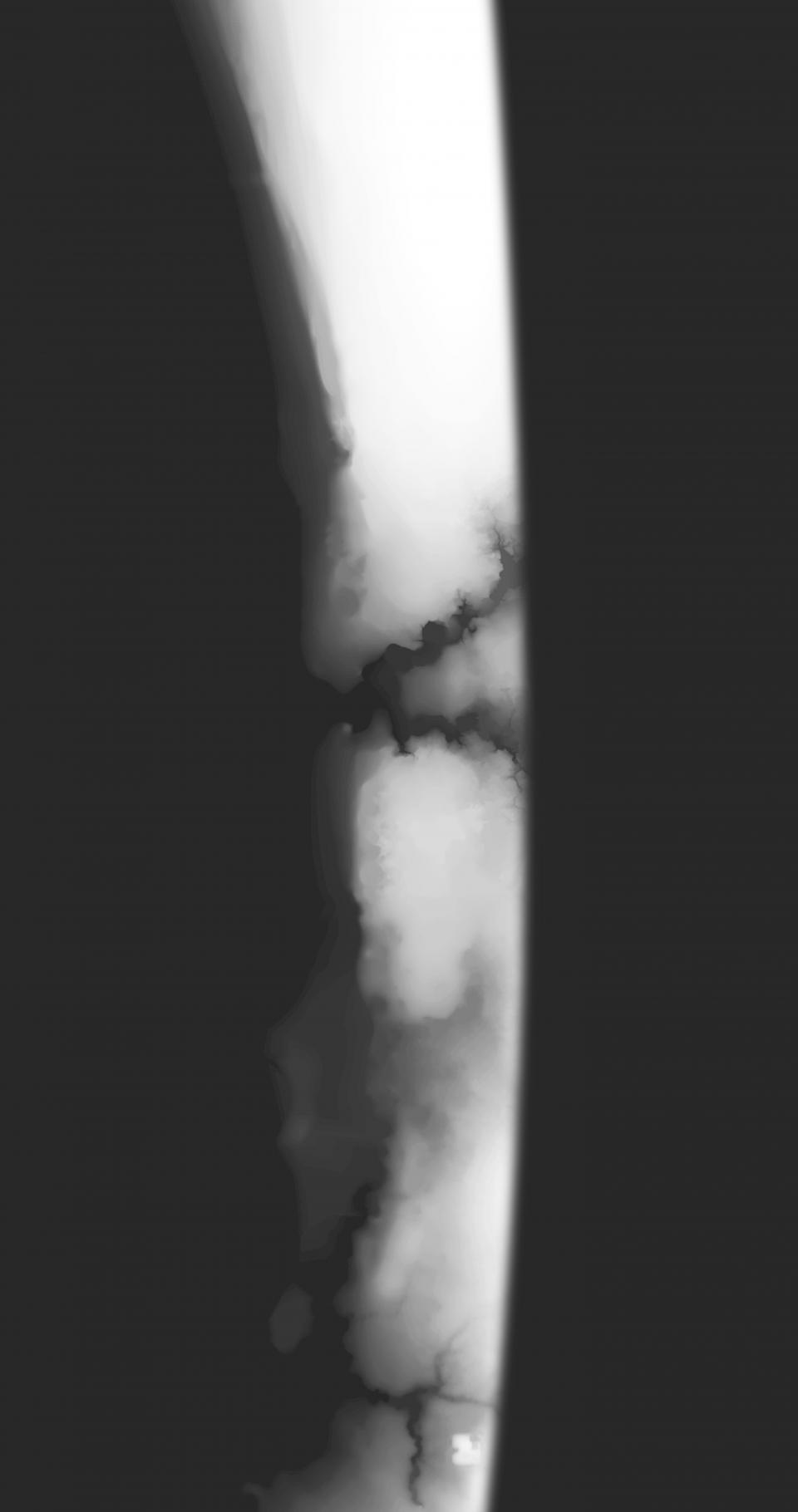

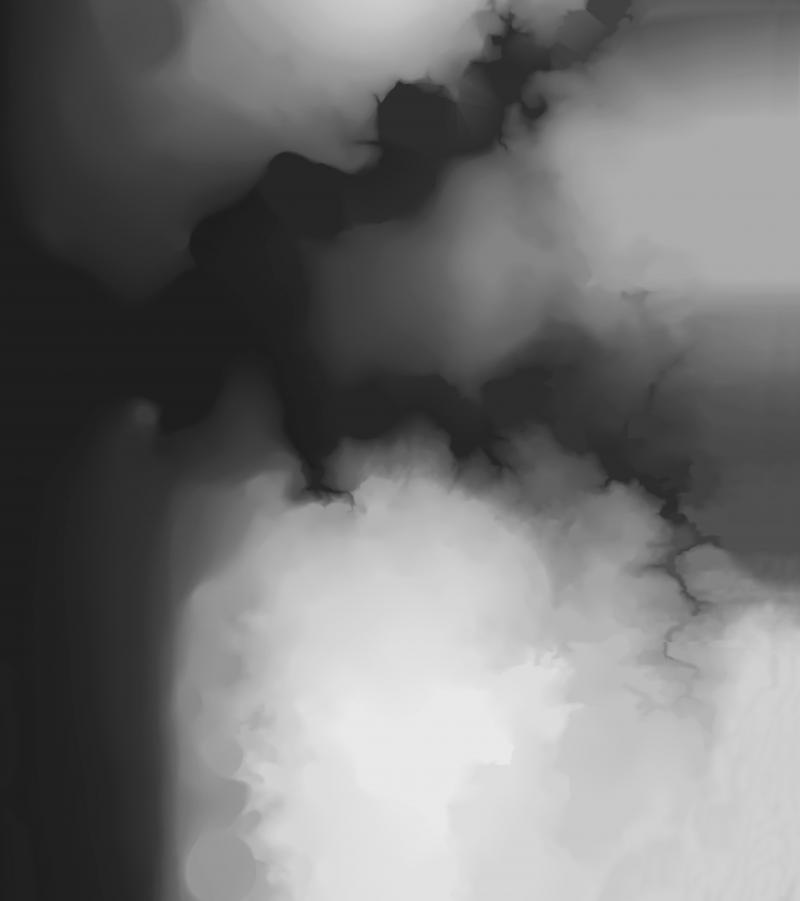

The form of the Swan River can be seen in this relief map of the superficial groundwater mounds beneath Perth. The lighter tones represent the higher groundwater elevations beneath the city surface. Image by Daniel Jan Martin, 2018.

The form of the Swan River can be seen in this relief map of the superficial groundwater mounds beneath Perth. The lighter tones represent the higher groundwater elevations beneath the city surface. Image by Daniel Jan Martin, 2018.

2018 Daniel Jan Martin

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Until the 1920s, water from artesian bores and the Victoria Reservoir in the Darling Range east of the city supplemented household supplies, but growing demand, inadequate supplies, poor water quality, and mounting public protest forced the government to dam additional streams in the Darling Ranges for urban water supplies. Over time, however, these dams proved inadequate in periods of drought and high water demand, prompting measures to curb water consumption. In the 1970s, water authorities also began to supplement dam water with groundwater drawn from the unconfined underground reserves beneath the suburbs.

From the 1970s, the onset of a regional drying trend increased the city’s reliance on these aquifers. Today, nearly half of the city’s potable water is drawn from aquifers, with the rest supplied mostly by desalination. This reliance has brought its own problems, as slowly unfolding subterranean crises have developed over time, hidden from view until they finally take a toll on the people and ecologies at the surface.

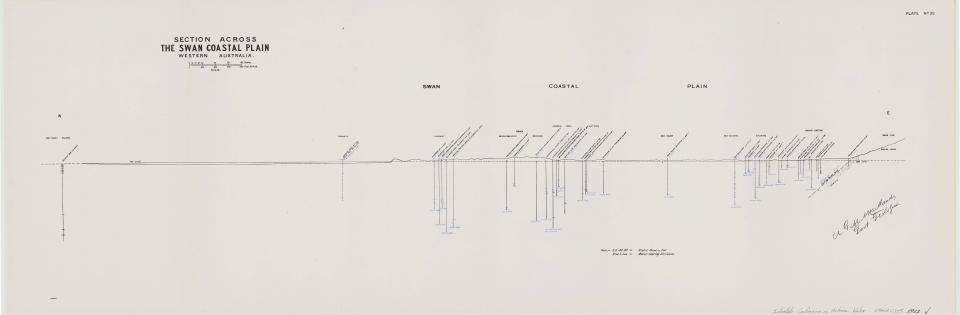

Early sectional surveys show an emerging awareness of the extents of groundwater beneath Perth. This mapping of groundwater depth and volume was produced by government geologist A. Gibb Maitland in 1912.

Early sectional surveys show an emerging awareness of the extents of groundwater beneath Perth. This mapping of groundwater depth and volume was produced by government geologist A. Gibb Maitland in 1912.

Graphic by A. Gibb, 1912.

Section across the Swan Coastal Plain, Western Australia / A. Gibb Maitland, Govt Geologist.

Plate no. 39 in “Report of the Interstate Conference on Artesian Water, Sydney, 1912.” Published:

Govt. Printer, Sydney, 1913.

National Library of Australia MAP G8971.C315 1912

Chart of Swan River from a survey / by Captn. James Stirling, R.N., 1827 National Library of Australia MAP T 1209.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

1970 Digging Deep

By the mid-1970s, Perth’s dams could no longer sustain the escalating demands of a population growing in size and prosperity. A decade earlier, international efforts to improve hydrological knowledge had encouraged Australian endeavors to undertake the long-awaited measurement of the continent’s water resources. In Western Australia, explorations of the Swan Coastal Plain around Perth revealed extensive stocks of water below the ground. Decades after the decision to obtain water from the streams of the Darling Ranges, the water authorities now believed that these groundwater reserves could be cheaply utilized to supply the suburbs.

With the first bore sunk in 1971, these aquifers soon provided about 10 percent of Perth’s water supply and experts predicted the city’s reliance on this source would grow. When harsh water restrictions and higher water prices were introduced later in the decade, many households responded by installing private bores or wells in their backyards. The only cost was sinking the well and keeping it maintained. By installing these private supplies, these households essentially gained access to virtually unlimited water for garden use, and, as a result, bore ownership in Perth trebled between 1976 and 1982.

These mappings of the Swan Coastal Plain show (i) Perth’s current urban area, (ii) the historic extents of the rivers, streams and wetlands which once covered the Perth region, and (iii) a visualization of the superficial groundwater mounds beneath the city (in this relief map, lighter tones represent the higher groundwater elevations). Images by Daniel Jan Martin, 2018.

Water authorities welcomed this boom in bore ownership: as half the average household consumption of water was being used in the garden, bores alleviated pressure to build more costly water infrastructure for the city. But, as not one of these bores was licensed, metered, or monitored, water use skyrocketed. One 1985 report estimated that a household with a domestic bore consumed over seven times the amount of water of a household dependent on public supplies.

By the end of the 1970s, then, both scheme water supplies and private supplies in Perth were being drawn from the subterranean treasure trove of groundwater beneath the suburbs.

Meanwhile, in the 1960s ecologists estimated that over half of the wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain had been lost already, and predicted that the public and private abstraction of large amounts of groundwater would endanger those that remained. They expected the draw on groundwater would threaten sensitive communities of flora and fauna, including migratory waterbirds. These concerns were realized in 1991 when large tracts of groundwater-dependent banksia woodland perished, prompting the water authorities to curb their pumping.

Black swans and other waterbirds on Lake Gwelup. Perth’s wetlands are expressions of the groundwater below and continue to support the city’s significant biodiversity. Photograph by Daniel Jan Martin, 2018.

Black swans and other waterbirds on Lake Gwelup. Perth’s wetlands are expressions of the groundwater below and continue to support the city’s significant biodiversity. Photograph by Daniel Jan Martin, 2018.

© 2018 Daniel Jan Martin

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

2001 Driest Winter on Record

As the drought of 2000–2001 took its toll on the city’s dams, groundwater again filled the gap, contributing over half of Perth’s water supplies. Water from the Gnangara Mound was pumped into Mundaring Weir to supply residents of the inland mining center of Kalgoorlie, six hundred kilometers away. The state government also offered households a financial incentive to install their own backyard bore, with information on the suburbs best-suited for private water supplies available from the 1997 Perth Groundwater Atlas. In 2009, about one in four Perth households had their own bore; their use was unlimited until 2007, when it was restricted to 3 days a week during the summer months. Market gardeners also faced new restrictions on the expansion of their properties from 2007, and found it necessary to sink deeper bores to reach the declining water table.

In the mid-1990s, Perth’s water managers had identified a regional drying trend since the 1970s, which had reduced the amount of streamflow into the city’s dams by nearly 50 per cent. It did not take long for the burden of greater consumption in a drying climate to take its toll on the already strained underground reserves and the wetlands that depend on them. Faced with the challenge of ecological triage, authorities pumped water into some areas, such as the Yanchep caves and Lake Jandabup, in the hope that this might revive them.

Perth’s Southern Seawater Desalination Plant converts seawater from the Indian Ocean to drinking water, to meet more than half of Perth’s scheme water demand. Photograph by Nearmap Australia Pty Ltd, 2019.

Perth’s Southern Seawater Desalination Plant converts seawater from the Indian Ocean to drinking water, to meet more than half of Perth’s scheme water demand. Photograph by Nearmap Australia Pty Ltd, 2019.

© Nearmap Australia Pty Ltd, 2019.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Ongoing questions about Perth’s water security in a drying climate dominated the 2005 election, and a year later a seawater desalination plant was completed at Kwinana to supplement the city’s water supplies. A second was finished in 2011.

2014 Saving the Aquifers?

In late 2012, the first reports of a worrying trend began to emerge: years of low rainfall, water abstraction, and thirsty pine plantations had combined to produce a sinking effect in Perth suburbs. These findings confirmed conservationists’ long-held suspicions that environmental authorities had inadequately policed the water abstraction of market gardeners and the Water Corporation.

Since 2014, the state government has invested in a groundwater replenishment scheme, which involves “recharging” the Gnangara Mound with treated wastewater. Perth residents have been more willing to stomach this process than their Queensland counterparts in Toowoomba, who rejected a similar proposal in 2006. Not only a less energy-intensive mode of water supply than desalination, recycling wastewater in Western Australia’s capital presents an alternative to the abiding dream of piping water from the state’s northwest. Satisfied with the first phase of the replenishment program, in 2017 the government began to pump recycled wastewater into the older Leederville and Yarragadee aquifers that lie beneath the Gnangara Mound.

Only time will tell if this approach will save the aquifers, while sustaining the water cultures of the people of Perth.

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive a gallery. View the photos below.

Orange stains caused by the iron-rich groundwater are commonplace across Perth. These enduring traces of Perth people’s reliance on bores for irrigation are here documented in a photo essay by Loren Holmes.

Photograph by Loren Holmes, 2018.

© 2018 Loren Holmes.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Photograph by Loren Holmes, 2018.

© 2018 Loren Holmes.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Photograph by Loren Holmes, 2018.

© 2018 Loren Holmes.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Photograph by Loren Holmes, 2018.

© 2018 Loren Holmes.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Photograph by Loren Holmes, 2018.

© 2018 Loren Holmes.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.