The Northwest Passage as a Question of Sovereignty

Highlights of this chapter

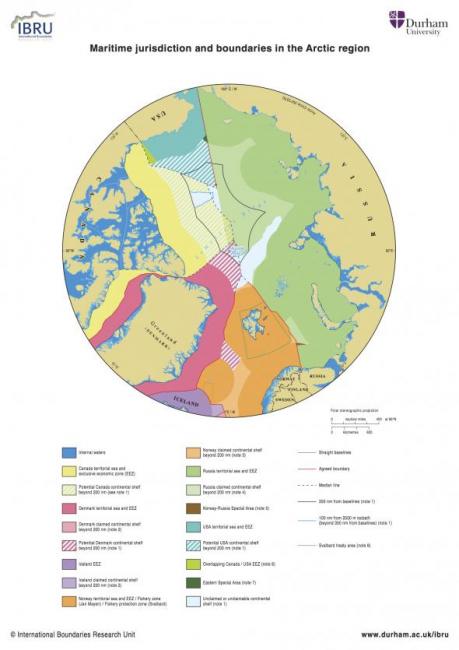

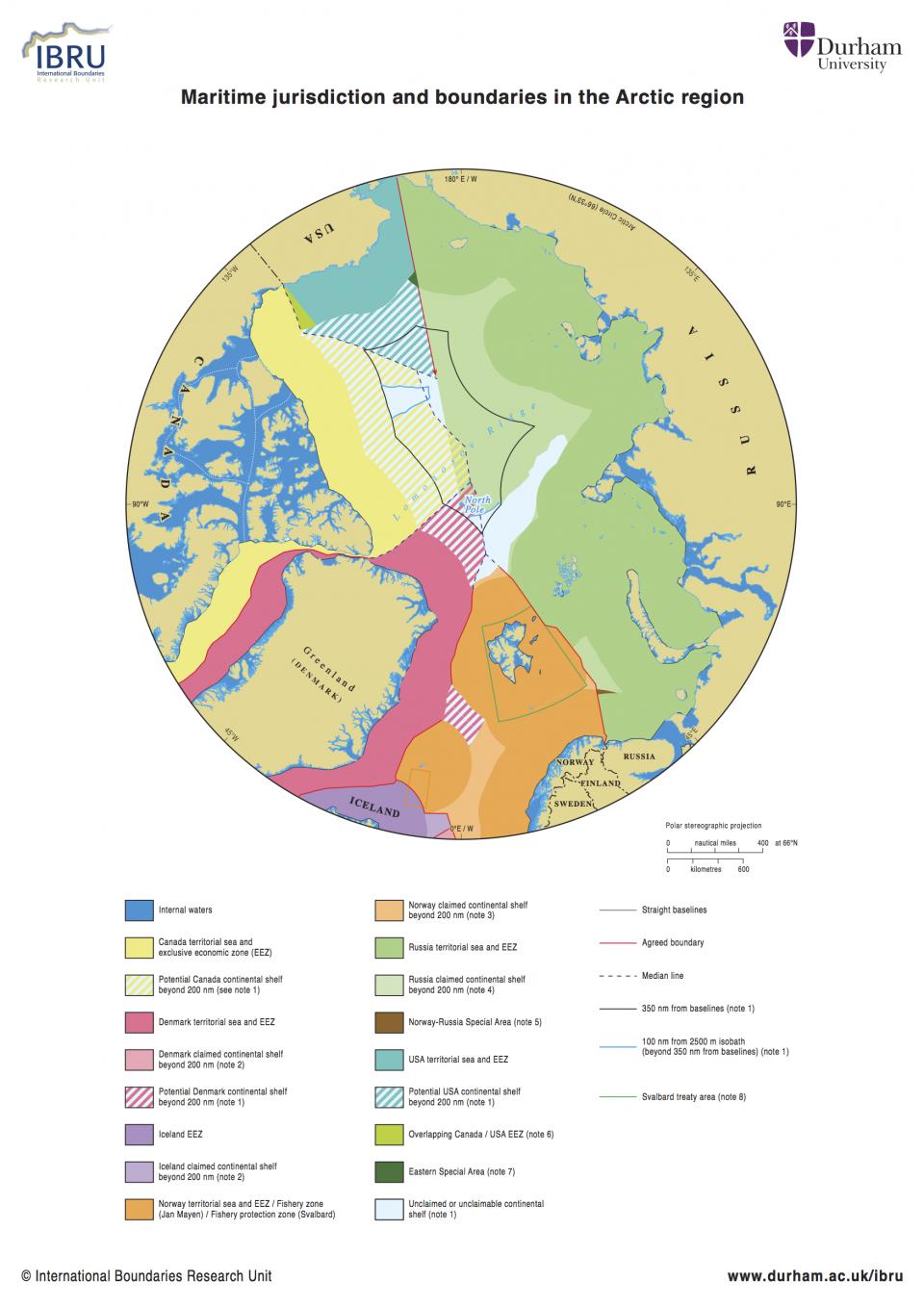

Mapping territorial claims

This chapter’s maps orient the reader to territorial claims in Arctic lands and waters. This colorful map shows maritime jurisdictions and boundaries, as well as potential future claims.

Maps of settlement sites

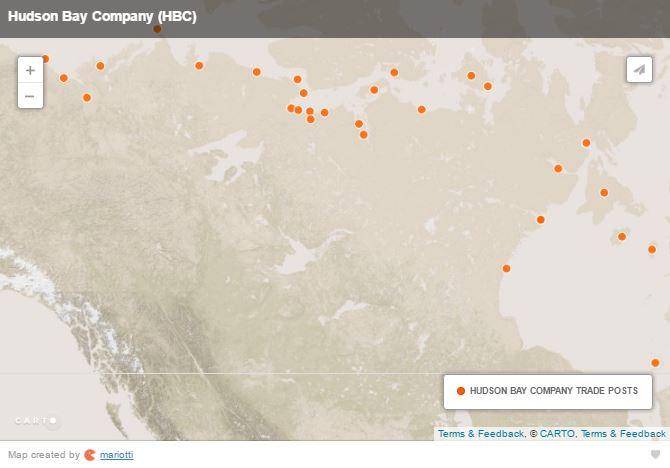

This map of Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts suggests choice of settlement sites that were an easy landing place or a meeting place for the Inuit in the area. Most posts became places of pilgrimage for fur trading.

Expert interviews

A video features several experts discussing the sovereignty question in relation to Arctic and Northwest Passage shipping.

Sovereignty

“Use It or Lose It”: Canadian Sovereignty in the Passage

United States

A Flag Beneath the North Pole: The Russian Point of View

External Actors

Indigenous Peoples

Sovereignty

The possibility of using the passage for shipping touched off a dispute between the United States and Canada, with the former claiming that the passage was an international waterway and the latter claiming sovereignty over much of the route.

Surface vessels and nuclear submarines have crossed the Arctic Archipelago since Roald Amundsen first navigated the Northwest Passage in 1903. The possibility of using the passage for shipping touched off a dispute between the United States and Canada, with the former claiming that the passage was an international waterway and the latter claiming sovereignty over much of the route. Canadian concerns took a more radical turn due to various factors connected directly with the relationship between the passage and Canadian identity.

In recent years climate change has increased the possibility of the development of new sea navigation routes to secure access to energy for Arctic petroleum extraction—considerably shortening the distance between Europe and North America to Asia—and has opened up new opportunities for fishing. All of these possibilities for exploitation, transport, and fishing have given rise to concern about the environmental risks connected to increased human activity and economic interests in the area, such as the threat to the traditional livelihoods of the indigenous populations.

The growing interest in the Far North has also increased the rivalry between the five Arctic states (USA, Canada, Russia, Denmark/Greenland, and Norway) over issues of sovereignty. At the same time, various international bodies of a private or governmental nature from areas like the European Union, China and Japan have shown interest in the area.

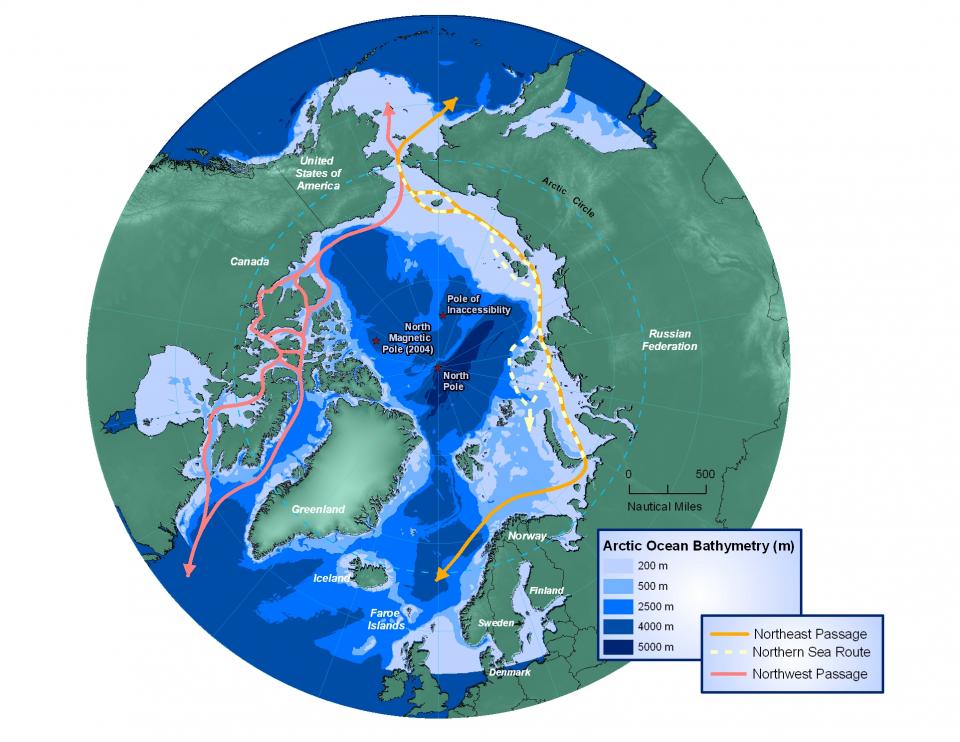

Today there are three shipping routes across the Arctic Ocean that offer great potential to transform commercial shipping in the twenty-first century: the Northwest Passage (NWP), the Northern Sea Route (NSR), and the Transpolar Sea Route (TSR). In addition, the Arctic Bridge, a shipping route linking the Arctic seaports of Murmansk (Russia) and Churchill (Canada), could also develop into a future trade route between Europe and Asia.

Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report, Arctic Council, April 2009”.

Clickhere to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

No. 19. Circumpolar routes. The map shows the different shipping routes across the Arctic. Source: Arctic Council, “Circumpolar Routes,” Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report, available at arcticdata.is.

The NSR off Russia’s northern coast is the only one of these routes that is extensively used. Under Russian law, all vessels must pay an “ice-breaker fee” for use of the NSR route. These fees are high and do not correlate directly to cost of the services rendered.

It is calculated that Arctic shipping routes could be 40 percent cheaper than traditional shipping via the Suez Canal. This means considerable savings on fuel costs, increased revenue, and potentially greater profit due to the lower number of days at sea and the possibility of a ship making a greater number of trips. Global shipping depends, however, on factors such as punctuality, predictability, and infrastructures, all of which are very difficult with the Arctic routes.

Arctic shipping is governed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the applicable established international law. Ratified by all the countries involved except for the United States, UNCLOS balances the different rights and responsibilities of states in their capacities as coastal, port, and flag states in the respective maritime zones.

Another organization that plays a key part in the international framework of UNCLOS is the International Maritime Organization (IMO), which is responsible for issues including safety and the control and prevention of vessel-source pollution and has already implemented two specific sets of recommendations for the Arctic. Most importantly, the IMO developed a mandatory Polar Code that entered into force on 1 January 2017.

An increasingly important feature of the legal landscape of marine infrastructure and offshore development in the Arctic as a whole is the Arctic Council. Created in 1996 under the terms of the Ottawa Declaration, this is an intergovernmental forum to foster cooperation, coordination, and interaction among the Arctic states with the involvement of the indigenous peoples of the whole circumpolar region. The member states are Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden, and the USA; in addition, it includes non-national bodies known as Permanent Participants, consisting mostly of indigenous peoples’ organizations.

Maritime jurisdiction and boundaries in the Arctic region. The map identifies known claims and agreed boundaries, plus potential areas that might be claimed in the future. Source: © 2008 International Boundaries Research Institute, Durham University, England.

Click here to view source.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

No. 20. Maritime jurisdiction and boundaries in the Arctic region. The map identifies known claims and agreed boundaries, plus potential areas that might be claimed in the future. Source: International Boundaries Research Institute, Durham University, England, 2008.

UNCLOS, the IMO, and the Arctic Council are all concerned with the Northwest Passage in different ways. The continental shelf and the mineral resources of its subsoil are another area of legal controversy involving the Arctic states. UNCLOS allows the states to claim an extended continental shelf of 200–350 nautical miles (370–650 km) from the baselines used to measure their territorial seas. Russia, Denmark, and Canada are currently engaged in making such a claim, which involves assembling scientific data and submitting it to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf within a certain deadline.

All the actors with an interest in the Passage have different opinions and perspectives on sovereignty over this area. In this context, the Inuit perspective is completely unique. In a world of shifting ice and harsh weather in which the movements of animals have no regard for borders, Inuit understand their surroundings in terms of cosmological and existential factors rather than political boundaries. Typical is the fact that, in Inuktitut, there is no word for “sovereignty.”

To translate the concept of sovereignty, the word aulatsigunnarniq, was used, which literally means “the ability to make things move,” in the context of being able to control something.

For thousands of years, Inuit had words for everything around them, perfectly articulating how they understood the world. When people came from other cultures, they brought not only their own morals and values with them, but also new words. To translate the concept of sovereignty, the word aulatsigunnarniq, was used, which literally means “the ability to make things move,” in the context of being able to control something.

In Inuit culture one cannot expect to impose geometry upon the world, since it is the world itself that dictates all conditions. Therefore, contrary to Western culture that opposes a rational, delimited order to undisciplined, imperfect chaos, Inuit culture does not fight against any perceivable chaos but rather works with and within an acceptable whole that has little to do with human rational tyranny.

The Inuit cosmological trinity Imaq–Nuna–Sila (Water–Land–Sky, each with a complex different meaning) does not leave man as a passive player at the mercy of a capricious world, but enables him, upon observation and adaptation, to participate in a dynamic system. In this system the True Human [Inummarik] acts as a sort of model, “a free human, sovereign over the self, respectful of the self-sovereignty of others. It is the human whose awareness not only renders self-sovereignty possible, but comprehends how self-sovereignties—those of others in society—synergize toward a system of self-perpetuating health.” (Rachel A. Qitsualik. Inummarik: Self-Sovereignty in Classic Inuit Thought in Nilliajut: Inuit Perspectives on Security, Patriotism and Sovereignty, 35. Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Inuit Qaujisarvingat, 2013.)

During the last century, in spite of this path, Inuit had to confront attempts and governments interventions used to assert sovereignty in the Arctic.

No. 21. Sovereignty. Video presenting the sovereignty question in relation to Arctic and Northwest Passage shipping. Interviewers underlined the connection between the historical problem and geopolitical issues. Video by Elena Baldassarri, August 2013, with interviews with Franklyn Griffiths, James Manicom, Adam Lajeunesse, John Higginbotham, and Kathrin Keil. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

“Use It or Lose It”: Canadian Sovereignty in the Passage

Various scholars have sought to underline how different meanings of sovereignty are used by the Canadian government to justify its territorial claims on the Arctic and the Northwest Passage. The challenge of the Passage is in fact one of self-discovery and self-definition for Canada in close connection with its claims on the Arctic.

Canada purchased the Hudson Bay territories in 1870 and received the consent of the British crown in 1880 to the transfer to Canada of “all British territories and possessions in North America, not already included within the Dominion of Canada and all Islands adjacent to any such Territories or Possessions.” There is nothing in this transfer to support Canada’s claims to sovereignty with respect to the United States or any European powers. The responsibility for consolidating Canada’s title was left to Captain Bernier’s voyages of 1904–11 and other government-funded expeditions.

The concept of sovereignty is somewhat elusive and changeable over time, with varying degrees of emphasis placed on different elements such as control, authority and perception.

The concept of sovereignty is somewhat elusive and changeable over time, with varying degrees of emphasis placed on different elements such as control, authority and perception. It is the central pillar of international law, and its definition reflects a state’s right to jurisdictional control, territorial integrity, and non-interference on the part of other states.

Sovereignty is connected, first of all, with topography. In this respect, the original topographic surveys of the Arctic waters are inadequate and this has not greatly improved over the centuries. Melting ice and increased accessibility have led to disputes between the bordering nations. In 2003 Canada ratified the UNCLOS, which grants states rights to the natural resources of the sea within the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles from the coast. Today Canada is mapping its continental shelf with a view to expanding its control over the Arctic.

In addition to geography, the concept of sovereignty in the Arctic involves aspects such as human presence, exploitation of the territory, and its military and environmental defense. The unusual feature of the Northwest Passage is that even if Canada enjoys undisputed possession of the islands, waters, seabed, and subsoil of the Arctic Archipelago, it still has to demonstrate its ability to control this territory. Canada argues that the Arctic waters of the Northwest Passage are “inland waters for historical reasons” and under Canadian jurisdiction, although this claim is disputed, especially by the United States and the European Union. As internal waters, they are subject to the sovereign will of Canada by virtue of a historical title transferred from Britain and from the Inuit people, who are now Canadian and have occupied the waters from the very outset. In short, Canada claims the historical right to grant or deny access to all foreign vessels—naval, commercial, and private—wishing to enter or sail through the Arctic Archipelago.

Canada also defines sovereignty in terms of responsibility. This includes the state of exercising control and authority over the territory, and the perception, by other states, of the presence of control. The political scientist Franklyn Griffiths defines sovereignty as “the ability of the state to exercise recognized rights of exclusive jurisdiction within a territorially delimited space.” In other words, sovereignty derives from the capacity for recognition and enactment: i.e., to secure recognition of one’s rights and to enact or act on these rights. Until recently, Canada has favored recognition over enactment in its approach to Arctic sovereignty.

An essential aspect of the assertion of Canadian sovereignty over Arctic waters regards the concept of the human dimension and is related to the presence of Native peoples. In particular, “use and occupation” by the inhabitants of northern Canada is significant in terms of sovereignty as enactment. This means that the country not only governs, but also “watches, keeps, takes care of and provides for in the running of things.”

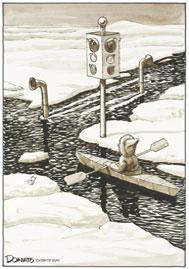

Encouraging Arctic development is also connected to the higher aim of securing Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic, by the logic of the motto “use it or lose it.”

In the last few years, the Canadian government has been encouraging Arctic exploration projects with the twin goals of demonstrating Canada’s effective occupation of its vast Arctic territory and improving the economic and social conditions of the local communities. The creation of jobs and the possibility of improving education opportunities and expanding social welfare systems are regarded as positive effects that in turn pay dividends in the form of increased tax revenues. Encouraging Arctic development is also connected to the higher aim of securing Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic, by the logic of the motto “use it or lose it.”

No. 22. Arctic traffic jam by Andy Donato. First published in the Toronto Sun, 1993. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner, Andy Donato.

United States

The US approach to the Arctic during the Cold War was linked to national security and continental defense. The USA has argued consistently that the Northwest Passage is an international strait (international waters) through which the vessels and aircraft of all countries have considerable rights of transit under the Law of the Sea. For this reason, it is reluctant to accept Canadian sovereignty over the Arctic, as this would threaten freedom of navigation, which is essential for US maritime activities worldwide, and would be contrary to the fundamental tenet that the Law of the Sea can be amended only by multilateral agreement. US efforts to limit any extension of the sovereignty of coastal states over the high seas in the rest of the world would also be impaired.

Supported by other delegations, the USA is particularly concerned that the Polar Code could provide an international legal basis for Canadian and Russian regulation of shipping traffic in the Arctic waters to which they lay claim. In future they will also play a decisive role in the prevention, control, and reduction of maritime pollution across all of the possible polar routes, because they will have the authority under general international law to impose conditions on the entry of foreign ships into their ports.

A Flag Beneath the North Pole: The Russian Point of View

The Russian Arctic encompasses 44 percent of the entire circumpolar area, according to the Arctic Council. Consequently, physical presence the North is pivotal to Russian identity, but in a different way to that of Canada: it is not a romantic, exotic concept, but a reality, and a big concern as has been expressed in past by historical Russian policy in the Arctic and today by the development of the Northern Sea Route. This route is not only a summertime operation, but a year-round transportation artery.

In recent decades Russian administrations have placed emphasis on increasing maritime traffic and maintaining control over the shipping lane, as well as financing first-class navy and naval bases. The navy is an instrument to protect national economic interests in the Arctic, where some of the world’s richest biological and mineral resources are concentrated.

In 2007 a Russian expedition deployed two submersibles to the ocean floor beneath the North Pole to collect samples and data, with the primary objective of gathering scientific evidence to support Russia’s territorial claims and, as a symbolic step, setting a Russian flag on the bottom of the seabed underneath the North Pole. This act raised wide concerns among international public opinion and governments, highlighting the uncertain legal status of the Arctic region.

The Kremlin has petitioned the UNCLOS Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to recognize Russia‘s exploration rights for the Arctic undersea territory, including the Lomonosov Ridge and Mendeleyev Ridges. The Russian claim is that the Arctic Ocean seabed is a projection of the Siberian continental shelf. The exploration and development of new offshore resources in the Arctic could present Russia with a vital opportunity to boost its gas and oil reserves.

From this perspective the Northern Sea Route is essential: most of the resources put into the route’s infrastructure are funneled into the Murmansk-Dudinka-Krasnoyarsk transport corridors. Murmansk is the largest city in the Arctic, in the far west of Russia, while Dudinka is a port on the Yenisey River. International shipping along the Northern Sea Route is posed to explode in the coming decades. Along with it, other facilities supporting marine transport will also expand, including intermodal connections, cranes, search and rescue capabilities, and weather satellites.

This image was taken by L. Murphy of the NOAA Ocean Explorer. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

No. 23. This image shows a Mir submersible. A similar submarine placed a Russian state flag in the seabed of the Arctic Ocean at a depth of 4,261 meters (13,980 feet). Russian newspapers lauded members of an Arctic expedition who planted a Russian flag in the seabed four kilometers (2.5 miles) beneath the North Pole.

External Actors

Each year marks a new record in the number of ships going through the corridor, but this is always minuscule in comparison to the other trade routes. Multi-year ice and the limited seasonal window for trans-Arctic voyages will constitute major obstacles in the future: trans-Arctic shipping routes will not be a substitute for existing shipping lanes but instead provide additional capacity for growing volumes of transportation.

In the past the European Union took little interest in the Arctic region, which was considered a peripheral area of little importance, especially after 1985 when Greenland formally withdraw from what was then the European Community. It was not until Finland and Sweden joined in 1995 and the EU Northern Dimension was created that interest in the Arctic was renewed.

The area’s new importance was evidenced in the 2007 report “On Strategic Issues Relating to the Arctic Ocean” and by the 2006 Green Paper “Towards a Future Maritime Policy for the Union,” which also discussed the problem of climate change. As the European Union is one of major parties involved in world trade, largely in the form of shipping, it has considerable interest in increased shipping capacity and potential alternatives to historical shipping routes. In particular, crucial importance is attached to trade between Europe and the Asian markets, and to the possibility of new routes to substitute or supplement the existing one through the Suez Canal. For this reason, many argue that the European Union should improve its policy in the region through an approach shared by all its member countries. This is not easy to achieve, however, due to the differing claims and interests within the EU assembly.

EU interest in the Arctic and in NWP shipping is dominated by the debate on issues including monitoring and surveillance, as well as the expansion of the tourism sector. Moreover, the EU approach still lacks an economic angle due to the unpredictability of future Arctic shipping.

The development of Arctic offshore resources and related economic activities will improve the integration of the Arctic economy in global trade. Each year marks a new record in the number of ships going through the corridor, but this is always minuscule in comparison to the other trade routes. Multi-year ice and the limited seasonal window for trans-Arctic voyages will constitute major obstacles in the future: trans-Arctic shipping routes will not be a substitute for existing shipping lanes but instead provide additional capacity for growing volumes of transportation.

In this race, powerful and interested parties such as China, Japan, and India have persistently increased their activity in the area through investments, economic cooperation, and research.

Indigenous Peoples

Sovereignty of the Arctic became a concern for Canada later, when international conflicts urged the Canadian government to assert their presence in the region. The Canadian Arctic Archipelago was inhabited largely by Inuit, and it was not until 1880 that an Order in Council confirmed to the Dominion of Canada the title and ownership of the Arctic Archipelago. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the government became worried about the presence of foreign vessels sailing between the Arctic islands, and funded several expeditions captained by J. E. Bernier and his Canadian ship, Neptune, to make annual tours along the Arctic coast and islands to collect navigational and scientific data and to declare Canadian sovereignty on many Arctic islands.

No. 24. This map shows the history of several trading posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Thanks to the trading post records available in the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, it was possible to determine the dates of opening and closing of each post. Note the choice of settlement sites that were generally an easy landing place or a meeting place for the Inuit in the area. Most of these posts became places of pilgrimage for hunters for fur trading. Over time mounted police bases and DEW Line military bases would be added, turning them into villages and finally into hamlets. A “hamlet” describes a municipal corporation with the status of a hamlet established by a governmental Act with a delineated geographical area of jurisdiction. All of Nunavut’s 25 municipalities are hamlets, except for the City of Iqaluit. This work was created by Enrico Mariotti in 2013 and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

To ensure control over land and water, beginning in 1920, the Canadian government facilitated Inuit relocations. In the first instance these relocations were motivated by subsistence needs, and Inuit were moved to regions with better natural resources to prevent starvation, but this procedure was soon boosted by sovereignty claims and economic concerns. To ensure success of its business, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) pressed the federal government for relocation projects that would group Inuit trappers near HBC posts across the Arctic. In 1953, however, the situation became distressing: relocations of Inuit families from Port Harrison (now Inukjuak) and Pond Inlet to Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord (Craig Harbor) produced big changes in Inuit communities.

The government exerted pressure upon Inuit to abandon their ilagiit nunagivaktangat (“camp”) and move into settlements, refusing to help those wanting to return to their land.

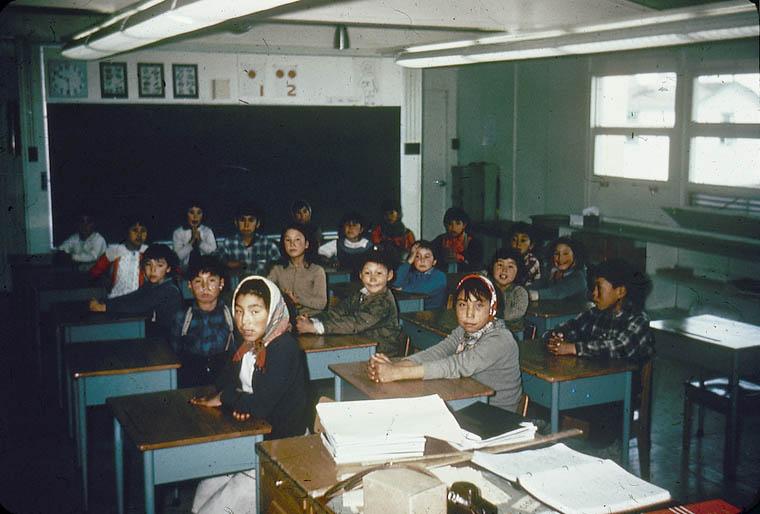

The motivations for the relocation were not clear for people who had to adapt to distant areas where they had no experience with the environment, the colder climate, or with the longer periods of total light or darkness. Even though Inuit had been migrating for centuries to follow seasonal routes, for trading or to maintain kinship networks, these changes were totally different. The government exerted pressure upon Inuit to abandon their ilagiit nunagivaktangat (“camp”) and move into settlements, refusing to help those wanting to return to their land. Worsening the situation was the government’s decision to provide school buildings and staff in the settlements, forcing Inuit to move there so their children could pursue education and have the opportunity to participate in the wage economy.

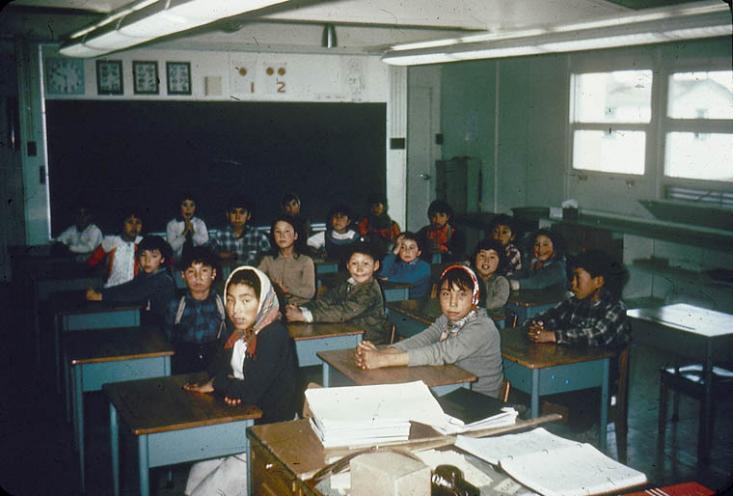

To accommodate children in the settlements, the government began building school hostels, supervised by Inuit, which were an alternative to sending young children to residential schools. The Indian Residential School (IRS) system grew out of Canada’s missionary experience with various religious organizations. The federal government began to play a role in the development and administration of this system as early as 1874 and ceased to operate them by the mid-1970s. Some parents tried to oppose the abandonment of traditional learning in favor of Western schooling, but they felt they had no choice when social workers, teachers, or Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers came to their ilagiit nunagivaktangit and told them “children have to go to school.”

Unidentified class of students Coral Harbour , N.W.T., [(Salliq), Nunavut], 1964. Health Canada fonds / Library and Archives Canada / © Library and Archives Canada.

Credit: Health Canada fonds / Library and Archives Canada / e002216411

Click here to view source.

No. 25. Unidentified class of students at Coral Harbor, Northwest Territories, [(Salliq), Nunavut]. Digital image. Health Canada fonds, Library and Archives Canada, 1964.

The impacts of these movements, relocations, and residential schools on Inuit society were inextricably linked to the Inuit sense of place and kinship. An entire generation of youth lost contact with the land and, as a result, a real understanding of Inuit culture, language and practices was also lost: the Inuit had no opportunities to exercise traditional knowledge and use their languages.

An entire generation of youth lost contact with the land and, as a result, a real understanding of Inuit culture, language and practices was also lost: the Inuit had no opportunities to exercise traditional knowledge and use their languages.

Inuit migrations between 1950 and 1975 were a mix of voluntary, pressured, and forced moves, usually in response to government priorities. These policies had long-term effects: Inuit felt deep cultural and personal losses resulting from family separations and ties to the land, and relocations altered their lives and made people vulnerable by forcing them to become dependent on government, thus diminishing Inuit self-sufficiency, self-esteem, and personal autonomy.

No. 26. The map shows the position of the hamlets in Nunavut and gives some information about their dates of incorporation. This work was created by Enrico Mariotti in 2013 and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Today, Canadian and US laws require consultation with the indigenous populations for all projects involving development and encroachment on lands or waters occupied and used from time immemorial by Native peoples. Land-claim agreements in Canada require any proposed project on the territory to have an impact-benefit agreement with the Native populations affected and seek their approval. In the USA, aboriginal consultations are required by former President Clinton’s Executive Order of 6 November 2000, and the First Nations have systematically used the US judicial system to defend their way of life and environment. Moreover, Alaskan and Inuit authorities are gradually making use of the traditional knowledge of the Native peoples in planning and carrying out projects concerning northern development. The proposals are very often in stark contrast to the environmental concerns of the indigenous people of the North, who see their traditional ways of life threatened by increasing external influences. In some cases, however, indigenous peoples are also calling for economic development with no unnecessary impediments because they see this as a way to obtain a more adequate economic position. This marks an important shift from merely environmental protection to a growing awareness that the consolidation and development of the Arctic societies must rest on economic development.

Tim Dolighan. Inuit Snub. Creation date: 29 March 2013. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner © Tim Dolighan. In http://dolighan.com/.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

No. 27. Tim Dolighan. Inuit Snub. Creation date: 29 March 2013. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner, Tim Dolighan.