The Northwest Passage as a Voyage to Myth and Adventure

Highlights of this chapter

Animated short film “Qalupalik”

This beautifully animated short film tells the story of Qalupalik, a part-human sea monster that lives deep in the Arctic Ocean and preys on children who do not listen to their elders. Ame Papatsie, 2010, National Film Board of Canada.

Evocative illustrations

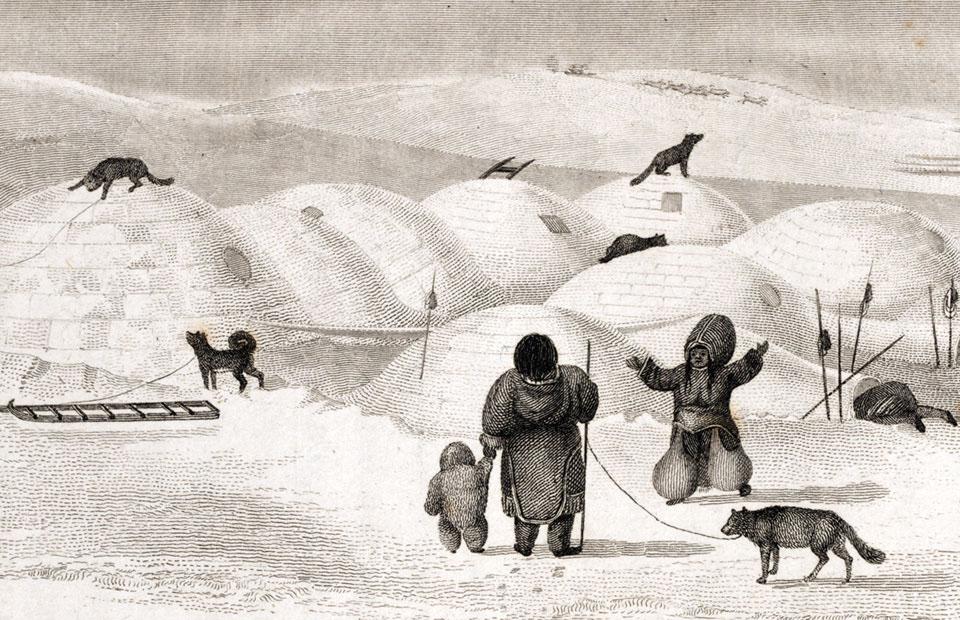

Illustrations like “An Inuit igloo village” by G. F. Lyon (1824) depict the people and landscapes that captured the imaginations of voyagers to the Arctic.

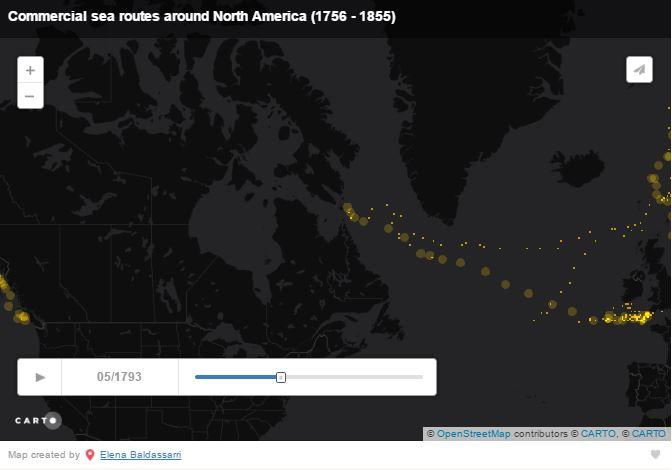

Dynamic maps

In this chapter, and throughout the exhibition, you can find dynamic maps showing events unfold over time. Elena Baldassarri created this animation, “Commercial sea routes around North America (1756–1855),” using the CLIWOC project dataset (Climatological Database for the World’s Oceans 1750–1850).

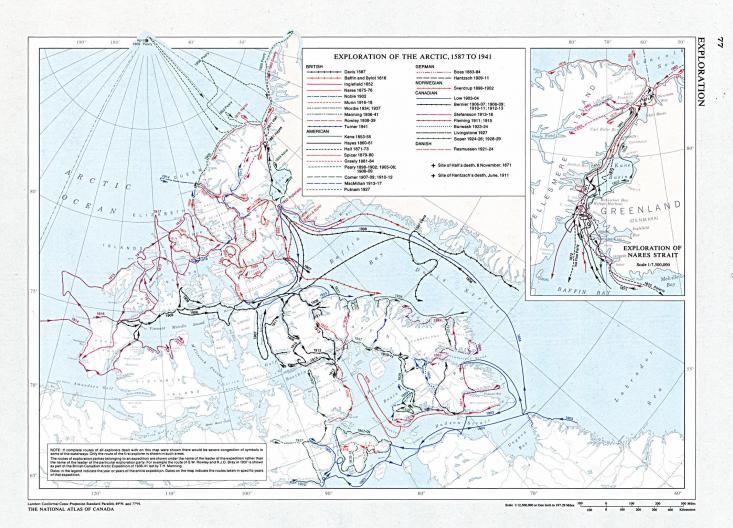

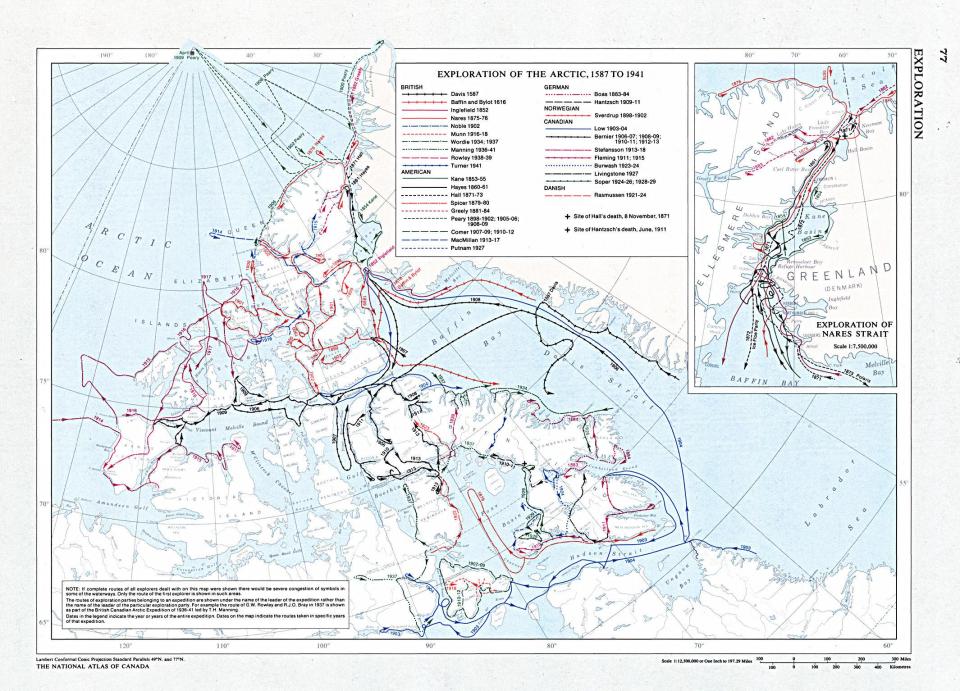

Captivating cartography

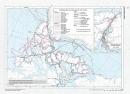

Bursting with maps new and old, the exhibition helps the reader visualize the region and its history. This map from the Atlas of Canada traces the different exploration routes in the Arctic taken by American, British, Canadian, Danish, German, and Norwegian explorers between 1587 and 1941.

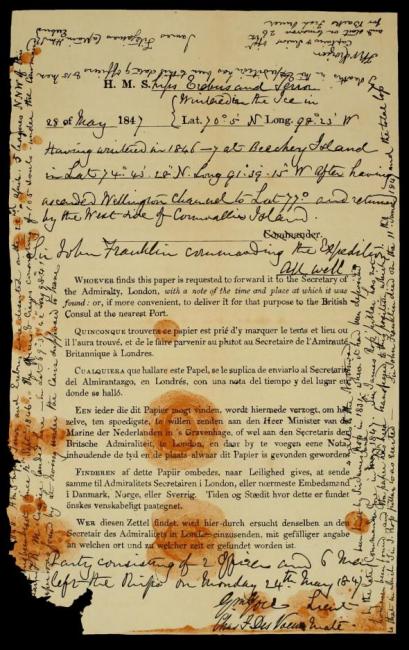

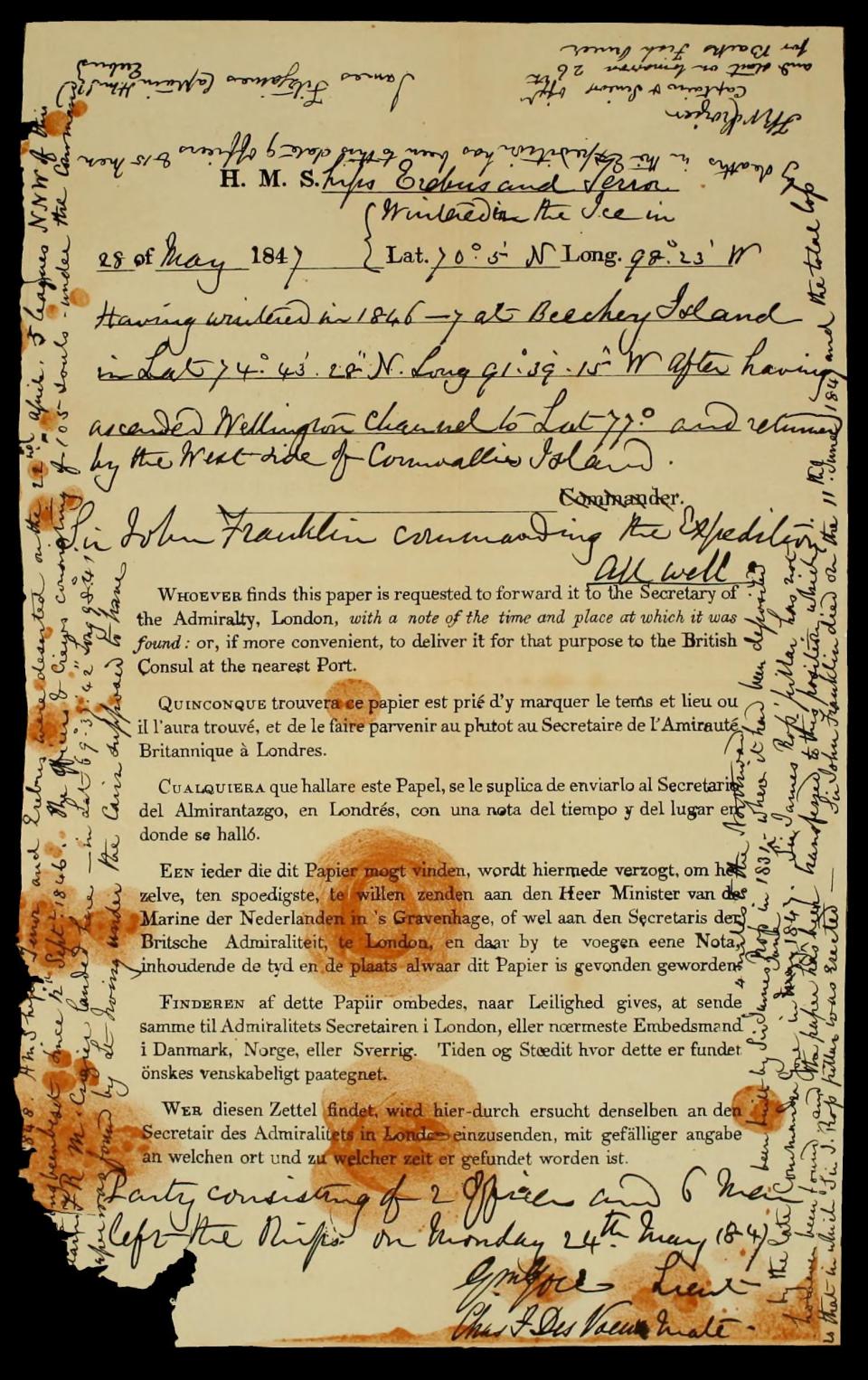

Devastating documents

On this weathered Standard Admiralty form, handwritten notes in six languages detail the fate of the Franklin Expedition’s HMS Terror and Erebus and the loss of 129 men. Missing for 168 years, the ships were discovered only in 2016.

Historical photographs

Historical photographs from the Arctic region and of Arctic explorers enrich the exhibition with a glimpse of the world more than a century ago. Photograph by George Lancefield, 1906.

Contemporary photographs

To show what Cambridge Bay and its surroundings look like today, exhibition curator Elena Baldassarri includes several recent photographs from her travels, such as this one depicting the remains of the Maud, explorer Roald Amundsen’s schooner, which sunk just in front of Cambridge Bay.

Myth

History

The Beginning (1497–1553)

In Search of the Anian Strait (1542–1677)

Elizabethan and Stuart Trading Ventures (1566–1634)

The Hudson’s Bay Company (1668–1791)

The Pacific Search Resumed (1761–1795)

The Royal Navy by Land and Sea (1815–1839)

Franklin’s Expeditions

The Passage Navigated (1903–1984)

Myth

Not many people have long stories—only short stories. Little stories, here and there. We don’t know much at all.

- Quoted in Dorothy Harley Eber, Encounters on the Passage: Inuit Meet the Explorers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008.

The myth of the Northwest Passage is part of the northern romance of the conflict between men and nature. In Western culture the North is not just a matter of geography but a place where humans are forged and strengthened, where cultural and technological progress seems useless without fortune and courage. The attitude of southerners to the North has traditionally been based on two different and conflicting perceptions: on the one hand a romantic feeling based upon the mysterious nature and power of the wilderness, but on the other a greedy desire to possess and exploit its resources.

The myth of the Northwest Passage is part of the northern romance of the conflict between men and nature. In Western culture the North is not just a matter of geography but a place where humans are forged and strengthened, where cultural and technological progress seems useless without fortune and courage.

The choices and decisions made in both the past and present in relation to the North in general, and to the Northwest Passage in particular, have been strongly influenced by mythology. In Canadian identity, for example, the harsh climate of the Arctic landscape served to create the image of Canada as a northern and vigorous country: “the true North strong and free,” as the national anthem puts it.

The frontier myth has deeply shaped and influenced human behavior and is present in the construction of the national identity of both the USA and Canada. The North has been, and still is, regarded as the last real frontier. This myth continues to influence the cultural and political ideas and economic ambitions of development and resource extraction at high latitudes, as well as the sovereignty and representations of Canada and the United States as a nation, place, and space.

In North America, the frontier was first identified by the historian Frederick Jackson Turner in his famous speech to the American Historical Association in 1893. Seen as an area of free land on the edge of settlements, into which pioneers and settlers advance, the frontier is the point where the “desert” or “wild” meets “civilization.” For Turner, the American West was a land of opportunity. He celebrated open spaces and wilderness, and often lamented its dissolution through domestication, regulation, and cultivation. In a sense, the frontier serves as a shifting boundary between the constant and domesticated, cultivated land, and the endless natural beauty of the wild. The border, according to Turner, has exerted great influence in the history of the United States: as a peripheral space it has defined the character of a nation. The definition given by Turner has also sparked immense debate amongst historians. Walter Prescott Webb stressed the difference in meaning between Europe and America: “The American thinks of the frontier as lying within, and not at the edge of a country. It is not a line to stop at, but an area inviting entrance. Instead of having one dimension, length, as in Europe, the American frontier has two dimensions, length and breadth. In Europe the frontier is stationary and presumably permanent; in America it was transient and temporal” (Walter Prescott Webb, The Great Frontier [Austin: University of Texas Press, 1952], 2–3). Webb added that “frontier” is not a static concept but rather a transitional one, geographically and temporally, stating that “inherent in the American concept of a moving frontier is the idea of a body of free land which can be had for the taking.”

Historians have also discussed the importance of Turner’s frontier thesis for the analysis of the development of Canada as a nation in the Northwest. First they point out that the border of the Canadian Northwest was different from that of the American West, a lawless land of hardy pioneers and Indians. By contrast, up until the second half of the nineteenth century Canadian “civilization” developed under the careful supervision of the government and Hudson Bay Company, which ran this immense territory before the arrival of settlers. Both frontiers, however, represent a “relief valve” of the wide open spaces against the pressure created by immigration in the cities. The settlers were immigrants from Europe, with the dream of a new life in a “promised land.”

Turner’s frontier thesis can help us understand the representation of the Northern frontier as a physical manifestation of “endless opportunities,” as a metaphor of progress that transcends physical and geographical space. With this interpretation, boundary, wilderness, and the frontier and its spatial and temporal implications, continue today to be an essential part of the image of the North in terms of its controversial nature and its transient state. For many, the frontier still exists in the Arctic, remaining vast, open, and free.

Climate change and melting ice have shed new light on the Arctic. Some commentators call it the last frontier for the extraction of oil, gas, and minerals, a frontier that is essential for the supply of the world’s growing energy needs. With global warming occurring on an unprecedented scale, it is widely believed that the melting of ice and permafrost will make access to the Arctic and its resources in the coming decades easier than ever before.

Is the Arctic the “last frontier?” To answer this question it is important, first of all, to recognize how popular knowledge of North American exploration and westward expansion has often been shaped by tales of heroic bravery, divine providence, and manifest destiny, even though the motives that have driven individuals in every century to undertake this venture have sometimes had more to do with economic gain and the rewards of discovery than with heroism.

As the world looks to the North for the exploitation of resources, new shipping routes and unprecedented opportunities for trade, scientists, politicians, Natives, and non-residents place the Arctic and its transformation into a transnational context as a pivotal part of the global economy.

This is nothing new for the North and its inhabitants, however, as they have a rich history of changes exerting a deep impact on their lives, including white European contact, relocation, changes in diet and the social effects of the loss of traditional knowledge.

All true wisdom is only to be found far from the dwelling of man, in great solitudes; and it can only be attained through suffering. Suffering and privation are the only things that can open the mind of man to that which is hidden from his fellows.

- Igjugarjuk to Knud Rasmussen. Quoted in Maria Coffey, Explorers of the Infinite (New York: Penguin, 2008).

In Inuit culture, myths and history come to us through legends: storytelling traditions are passed from generation to generation, linking people to their cultures and ancestors. Traditional stories are an important aspect of Inuit culture: Inuit myths and legends are usually narratives in dramatic form that deal with the wonders of the world, creation, love, hunting, respect for parents and elders, death, and mystery. Inuit believe in other worlds beneath the sea, the Earth, and in the sky from which new creatures come and where angakoks (shamans) have the power to move in trances and dreams.

These stories express the frontier between human and spirit: protagonists are spirits and shamans, and describe the fears and significant moments of the people. Even if, in Inuit culture, there is no “frontier” between humans and animals, because spirits pass throughout each form, some “borders” are fixed and must not crossed, regardless of the consequences.

No. 5. Nanavut Animation Lab: Qalupalik. This animated short tells the story of Qalupalik, a part-human sea monster that lives deep in the Arctic Ocean and preys on children who do not listen to their parents or elders. That is the fate of Angutii, a young boy who refuses to help out in his family’s camp and who plays by the shoreline, until one day Qalupalik seizes him and drags him away. Angutii’s father, a great hunter, must then embark on a lengthy kayak journey to try and bring his son home. Qalupalik. Ame Papatsie, 2010, 5 min 34 s. National Film Board of Canada.

One legend, recorded in the Kitikmeot region, describes the moment when the most important border was established: the one between life and death. This legend, called Uvajuq, retraces the Inuit genesis and was collected from a group of elders in the Community of Cambridge Bay. The story took place when people and animals lived in such harmony and unity that they could speak to each other. For Inuit this idyllic existence came to an abrupt end a long time ago.

And still,

both people and animals lived on Earth,

but there was no difference between them…

A person could become an animal,

and an animal could become a human being.

There were wolves, bears, and foxes

but as soon as they turned into humans

they were all the same.

They may have had different habits,

but all spoke the same tongue,

lived in the same kind of houses,

and spoke and hunted in the same way.

That is the way they lived here on Earth

in the very earliest times,

times that no one can understand now.

That was the time when magic words were made.

A word spoken by chance would suddenly

become powerful, and what people wanted

to happen could happen, and nobody could explain how it was.- Naalungiaq, 1923

Uvajuq was a giant who led his family on a quest for survival by walking across Victoria Island. The family of giants all perished, and their bodies created the hills that today mark the flat landscape near Cambridge Bay known as Uvajuq. The story goes on to describe how those facing starvation fought among themselves to the death; those who shared with one another, by contrast, survived. The legend is an allegory based on the Inuit philosophy of how sharing has given them strength to survive through the centuries.

History

Many talented men set out to prove the existence of the passage, not only by sailing and risking their lives on the northern waters but by exerting influence, writing, publishing, and financing expeditions of discovery.

The history of the search for the Northwest Passage stretches over five centuries. The discoveries and visionary undertakings stimulated by the possibility of a commercially and strategically advantageous seaway have become the symbol of the struggle between the best of Western civilization and nature, pitting courage and technology against the rigors of the Arctic environment. Many talented men set out to prove the existence of the passage, not only by sailing and risking their lives on the northern waters but by exerting influence, writing, publishing, and financing expeditions of discovery.

There are some aspects that have not changed since John Cabot’s first attempt to reach Cathay in 1497. The interest in this remote part of the world is driven by two contemporary forces that are crucial to the success of any enterprise: on the one hand, the courage of a few men who risk their lives in their attempts, and on the other the constant subterranean work of men to convince public opinion as well as sovereigns, governments, and financiers of the benefits of the venture.

The Beginning (1497–1553)

England was the first, and certainly the most active, country to search for the Passage, primarily because of the advantages offered by its geographical location. The fruitless search for a passage to the Indies in the central and southern regions of the New World and the consideration, after Magellan’s voyage, that the southern route existed but was also distant and difficult, left the possibility of finding another passage in North America or Eurasia as the only alternative to accepting the Portuguese and Spanish dominance.

The first real attempt to find a passage to circumnavigate the new continent was made by the Portuguese mariners Gaspar and Miguel Corte-Real.

France, too, joined the race. Emulating the other kingdoms, Francis I approved the voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano and Jacques Cartier to explore the coastline of North America in search of a channel through the continent.

The discovery and exploration of the Americas by Europeans and the subsequent effort to control and divide those lands revived interest in scientific mapping methods. The cartographers Diogo Ribeiro, Gerardus Mercator, Gemma Frisius, and Bolognino Zaltieri contributed to a vast collection of maps influenced by the information collected on the voyages of exploration.

Credit: Canadian Government

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under the Open Government Licence - Canada.

No. 6. Routes of Explorers. Contained in the second edition (1915) of the Atlas of Canada is a map showing the routes followed by the principal explorers from 1497 to 1906. Each route is marked as a red line on the map, giving the name of the explorer or company, and the dates on which each person traveled the route. The map also provides the dates of the founding principal forts and trading posts of the French, Hudson’s Bay and North West Companies. Atlas of Canada, Canadian Department of the Interior, 1915. In Routes of Explorers.

In Search of the Anian Strait (1542–1677)

In the second half of the sixteenth century, interest switched to the western part of the new continent. Spain and England started a new race to find the passage from the Northeast in the mistaken belief that Asia and America were in the same place separated only by a channel, the Anian Strait.

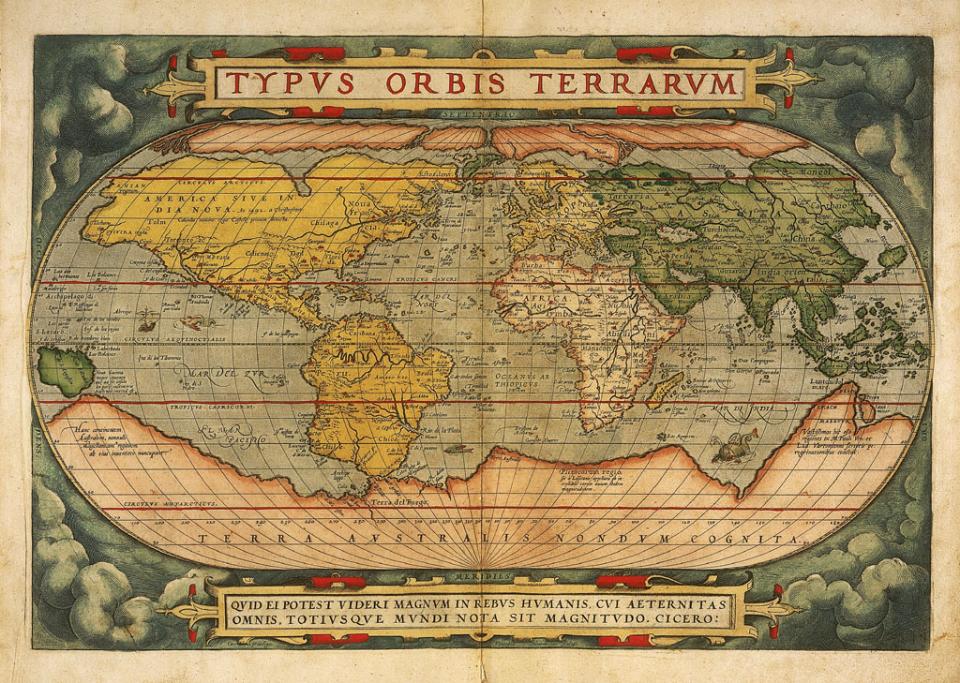

Belief in the existence of the Anian Strait was strengthened by the publication of maps and pamphlets such as Giacomo Gastaldi’s Universale Descrittione del Monde and the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of Abraham Ortelius, which described a strait separating the two continents of Asia and America, albeit in confusing and ambiguous terms. All of the maps showed that the passage would be easy to navigate.

Public Domain. Courtesy of Universität Bern. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

No. 7. Typvs orbis terrarvm [Kartenmaterial]: cum privilegio / Franciscus Hogenbergus sculpsit. Abraham Ortelius and Frans Hogenberg, Typvs orbis terrarvm cum privilegio. [Antwerpen]: [s.n.], 1573.

The Anian Strait remained on maps for several centuries, albeit in different locations, as the western end of a Northwest Passage. While it was obviously never found—as no such strait exists—the search for it led to the exploration of the Pacific coast from California to the Bering Strait.

Elizabethan and Stuart Trading Ventures (1566–1634)

The first concrete explorations to reach the Passage started from England in the second half of the sixteenth century. For half a century English navigators risked their lives in the icy seas of the Arctic and along the northeast coast searching for a route to the Pacific. English merchants, politicians, seamen, and adventurers, such as Humphrey Gilbert, regarded the search for a Northwest Passage as a means of breaking the Spanish hold on the spice trade and on the riches of the New World. Their pressure towards a possible imperial destiny for England was finally supported by Queen Elizabeth I, and through changes in policy and diplomacy.

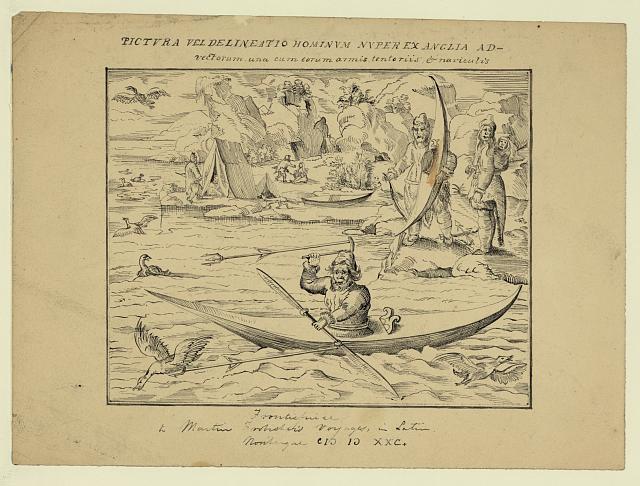

Martin Frobisher left England in 1576 on the first concrete and well-planned English attempt to find the Passage. He sailed from the southern coast of Greenland across the Davis Strait to a latitude of 62° N, and was convinced that he had found what he was looking for. In actual fact, as he realized on his subsequent voyage, it was just a long fjord on the southeast coast of Baffin Island, which bears his name today.

Credit: Library of Congress, Washington.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

No. 8. Frontispiece of Frobisher’s Historia Navigationis. Pictura vel delineatio hominum nuper ex Anglia AD vectorum una cum corum armis tentoriis, & naviculis. The drawing is a modern copy of the frontispiece to Frobisher’s Historia Navigationis, an account of his travels to the Davis Straits area of Greenland in the 1570s. It shows an Inuit hunting birds from a kayak, while another man holds his kayak on the shore. An Inuit woman carries her infant on her back. To the left is a village scene with tents, Inuit families, and a dog harnessed to a kayak, pulling it along. “Pictura vel delineatio hominum nuper ex Anglia AD vectorum una cum corum armis tentoriis, & naviculis.” Drawing. Between 1850 and 1920. From the Library of Congress: Documentary Drawings Collection.

On Baffin Island, Frobisher and his men met, for the first time, Inuit—in kayaks—who considered Westerners to be enemies. Five of the crew disappeared while returning an Inuit hostage, and, before he departed, Frobisher managed to kidnap an Inuit kayaker by using a hook on a pole. Frobisher brought him to England, where he was publicly displayed as a “strange man of Cathay” showing his resemblance to Tartars as proof of the existence of the passage. The Inuit died within a few weeks of landing in London.

When the ship was spotted, the Inuit took their kayaks and went to meet the ship. They had never seen such a big ship and the people were strange, just different. Right away there were some grudges. The Qallunaat fired two warning shots in the air. I’m sure the Qallunaat had good intentions, but they had never seen Inuit before and Inuit had never seen Qallunaat. So when they met there was a lot of uncertainty. The Inuit were scared. They didn’t want to give in to these people because they didn’t know what they were. Because they weren’t quite Inuit. And their clothes—how they dressed! The Inuit dressed in sealskin or caribou skins. The Qallunaat looked so different. They were different beings. The Inuit had never seen clothes like that. At first contact Inuit thought, “How come they dress like this?” It’s very cold; their clothes are not fit for this kind of weather. They used to wonder… They were ghostly.

- No. 9. The stories of the first encounter between Europeans and Inuit as told by the elder Inookie Adamie of Iqaluit. Reported in Dorothy Harley Eber, Encounters on the Passage: Inuit Meet the Explorers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008. In this Soundcloud recording produced by Elena Baldassarri, the text is read by Ana Shorter.

After a pause in exploration activities due to the need to safeguard the homeland against the Spanish attempt of invasion with the Armada (1587–88), interest was rekindled in the 1580s. Humphrey Gilbert, Walter Raleigh, and John Davis all undertook expeditions along different routes. Their experiences revealed the morphology of the Arctic regions but also began to show that the search would be much more difficult than expected.

To encourage exploration and to seek funds for such endeavors, gentlemen and members of the British elite published several books about the voyages. These efforts molded public opinion and attracted government attention and went on to encourage the writing of narratives of polar voyages in the years following.

A dramatic attempt was made in the service of the English crown by the Dutchman Henry Hudson, one of the greatest explorers of the northern regions, who reached the bay that now bears his name in 1610 but was then forced to halt by the onset of winter. He wanted to resume explorations the following spring, but his exhausted men mutinied and sailed away with the ship, leaving him in a small boat with a few companions.

The Hudson’s Bay Company (1668–1791)

It was the English Hudson’s Bay Company that gave new impetus to the quest for a Passage, albeit reluctantly, at the end of the seventeenth century. The company had been founded in 1670 by Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers, two French traders excluded by the French monopoly of the fur trade who consequently joined forces with an English partner to set up a trading post on the Hudson Bay, northwest of Lake Superior.

While the Hudson’s Bay Royal Charter specifically mentioned the company’s mission to seek the Northwest Passage, for the first thirty years of its existence this aim took second place to the fur trade south of the Hudson Bay. It was not until the eighteenth century that the company was forced to take part in a sustained effort to find the passage from the bay with the voyages of James Knight, Samuel Hearne, and Christopher Middleton, thus surviving the political pressure of critics seeking to end its trading monopoly.

The Pacific Search Resumed (1761–1795)

All these explorers left important information in terms of geographical discoveries but the passage remained as elusive as ever.

Even though Hearne’s journey along the Coppermine River had demonstrated the non-existence of a passage through Hudson’s Bay, the Anian Strait was still believed to offer a possible route.

The Spanish resumed their search for a Pacific entrance to a northern seaway in the second half of the eighteenth century, largely because of their fears of Russian invasion and English intrusion.

British, French, Spanish, and Russian navigators started a series of voyages to map and mark out the territory with the aim of finding a passage that would threaten strategic control of the coastline of northwest America and establish or consolidate trade in the Pacific.

The voyages of John Byron, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, James Cook, Alejandro Malaspina, and George Vancouver took place in this context. All these explorers left important information in terms of geographical discoveries but the passage remained as elusive as ever. Russian exploration established that Asia and North America were separated by the open seas and that the Anian Strait, now named the Bering Strait, was further northwest than had been thought. English hopes and Spanish fears of a navigable and commercially useful passage were still, however, prevalent.

No. 10. Commercial sea routes around North America (1756–1855). This map was created using the CLIWOC project dataset (Climatological Database for the World’s Oceans 1750–1850). The principal objective of the CLIWOC project was to recover information on climates over the ocean in the pre-instrumental period using abundant meteorological data from the logbooks of different European countries. The analysis of the logbooks’ content contributed to the characterization of climate during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and to the assessment of climate change. For more information about the project check CLIWOC. This map extrapolates from records of the passage of British vessels, focusing on their position (latitude and longitude) with the purpose of demonstrating graphically the intensity of the commercial passage through the north in the period 1750–1850. In doing so, we must consider that not all the vessels are recorded in CLIWOC. However, the data provide a picture of the behavior and interests of the Navy towards the Arctic. The map shows the high priority the Royal Navy granted to the Northern route during the second half of the eighteenth century, displaying the activity in the Pacific in the 1780s. A slowing-down during the Napoleonic wars and the Anglo-American War of 1812–14 is also noticeable. This work was created by Elena Baldassarri in 2014 and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The Royal Navy by Land and Sea (1815–1839)

After the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the British government renewed its efforts under the initiative of John Barrow, second secretary of the Admiralty. A powerful man firmly convinced of the existence of a navigable passage, Barrow sought to persuade the British government and public that its discovery was a matter of national interest for the empire and therefore a duty for the Royal Navy.

His efforts were strengthened by speculation that a general reduction of the Arctic ice barrier might have occurred, and that shipping at higher latitudes had become possible. The sustained efforts of the Royal Navy enabled progress with mapping unknown regions.

One of the first attempts was made in 1818, when Captain John Ross sailed with ships of the Royal Navy under instructions to proceed north to the Davis Strait and explore Baffin Bay. His conclusion that this could form no part of the passage created a great deal of controversy.

Ross was followed by William Edward Perry. Having arrived at longitude 112° west, where nobody had ever been before, he was halted by the barrier of permanent ice and forced to turn back. It was a remarkable success, but still the Passage remained to be discovered. His experience nurtured a great literary production based on his journals and the memories recorded by his crew.

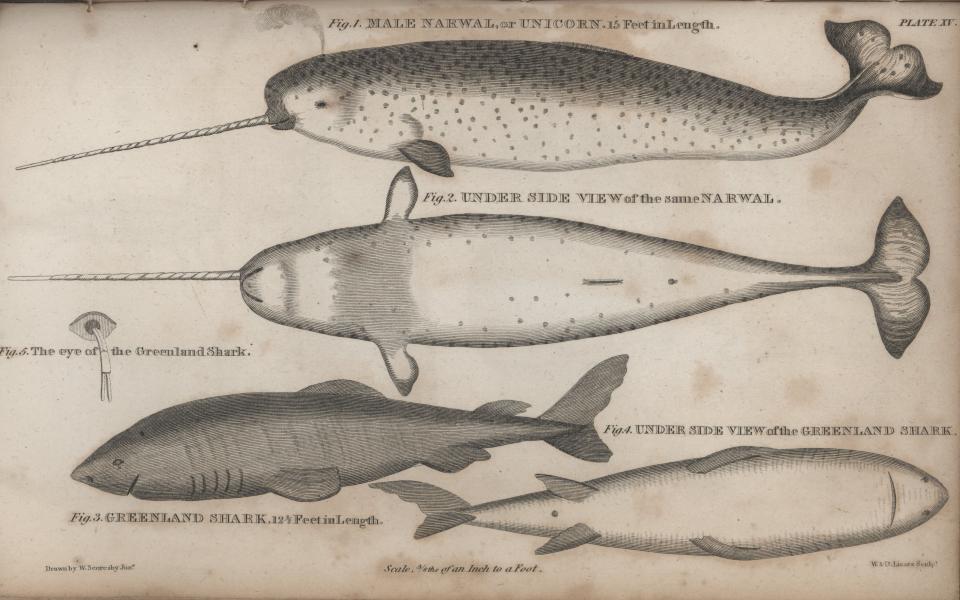

“Male narwhal or unicorn. Greenland shark.” In: Scoresby, William. 1820. An account of the Arctic regions with a history and description of the northern whale-fishery, 588, Vol. II. Plate XV. Library Call Number G742 .S42 1820. Printed for Archibald Constable and Co. Edinburgh: and Hurst, Robinson and Co. Cheapside, London.

Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce.

Source: NOAA Library Collection.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

No. 11. Male narwhal or unicorn. Greenland shark. In: W. P. Scoresby, “An Account of the Arctic Regions with a History and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery,” 588, Vol. 2, Plate 15. Library Call Number G742. S42 1820, 1820. Source: NOAA Library Collection. The narwhal’s [Monodon monoceros] range is west of Greenland to eastern Canada (Hudson and Baffin Bays) as well as northern Russia. The Greenland shark [Somniosus microcephalus] is a large, coldwater shark that lives in very deep water from the North Atlantic to the coast of Maine. Source: NOAA Library Collection.

In this period, whaler captain William Scoresby published his observations of natural phenomena in the Arctic as the book An Account of the Arctic Regions with a History and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery. He also mapped and charted the east coast of Greenland on his voyage in 1823. In the same years, George Francis Lyon published an account of his adventures on Parry’s voyages, where he described an Inuit igloo village and observed closely the Inuit use of dogs for sledging.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

No. 12. An Inuit igloo village, by G. F. Lyon, The Private Journal of Captain G.F. Lyon, of HMS Hecla during the Recent Voyage of Discovery under Captain Parry. Boston: Wells and Lilly, 1824.

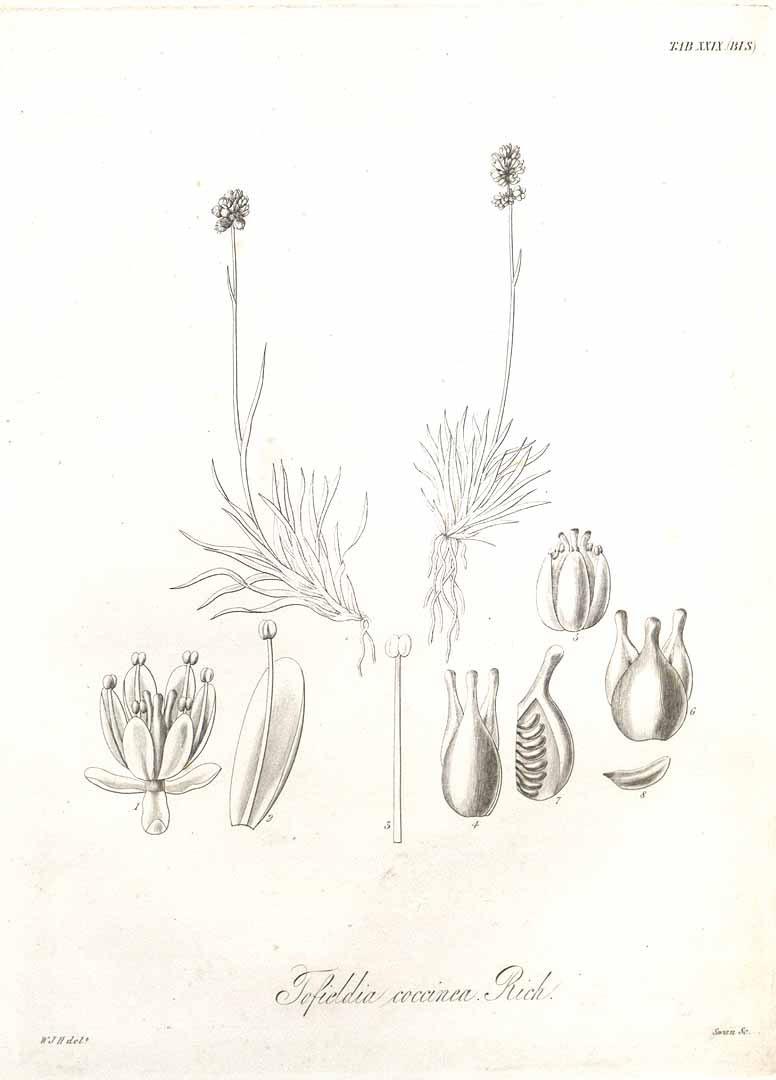

John Franklin penetrated land in two expeditions to map more than 1800 miles of Canadian coastline. The ambitions of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Royal Navy mission led up to deeper geographical discoveries in the Arctic, including the discovery of the North Magnetic Pole by James Clarke Ross. Thanks to William Jackson Hooker the British government agreed that botanists could be appointed to expeditions in order that English herbariums received large and valuable additions from all parts of the globe, and some books recording the natural effects of the voyages were published.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

No. 13. Tofieldia coccinea Richardson. In William Jackson Hooker, George A. Walker Arnott, and Frederick William Beechey, The Botany of Captain Beechey’s Voyage Comprising an Account of the Plants Collected by Messrs. Lay and Collie, and Other Officers of the Expedition, during the Voyage to the Pacific and Bering’s Strait, Performed in His Majesty’s Ship Blossom, under the Command of Captain F. W. Beechey, R. N., F. R. S., & A. S., in the Years 1825, 26, 27, and 28. London: H.G. Bohn, 1839.

Franklin’s Expeditions

Explorations of the Arctic coastline seemed to show that discovery of the Northwest Passage was imminent. Determined to be the man who succeeded, Sir John Franklin led three expeditions, from the last of which no one returned alive. He sailed in May 1845 with the ships Erebus and Terror and a crew of 129; in late July they were seen by a whaler in Baffin Bay, waiting for the ice to clear in the Lancaster Sound so that they could begin their journey to the Bering Strait.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

No. 14. The final Franklin communication found by Hobson and McClintock in May 1859 in a cairn south of Back Bay, King William Island. From Francis Leopold McClintock, The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ in the Arctic Seas a Narrative of the Discovery of the Fate of Sir John Franklin and His Companions. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1860.

The second part of the nineteenth century saw a constant stream of expeditions to search for John Franklin and his companions. At least thirty expeditions were made with no success, and many died in their attempts.

Each expedition added a new element to our knowledge of the Canadian Arctic, and it soon became clear that the route was more difficult than crossing the Southwest and thus was, in practice, unusable.

Each expedition added a new element to our knowledge of the Canadian Arctic, and it soon became clear that the route was more difficult than crossing the Southwest and thus was, in practice, unusable. The first expedition to cross from the Bering Strait to the Davis Strait, albeit traveling from west to east, was that led by Robert McClure, who arrived in the Arctic in 1849 in search of the Franklin expedition. It was not an easy task: Franklin and his men were not found, and McClure’s ship became stuck in the ice so that he was forced to proceed by sleigh to Melville Island, where he was rescued by another expedition patrolling the area.

The way my father told it they buried their leader, the captain, on a hill—on the rocks—somewhere on the northwest of King William Island. They gave him a proper burial. They buried him with respect. There was a proper burial in the north of King William Island. Or somewhere else. Nobody knows exactly where. A lot of people went looking for him but nobody ever found him. In the same place, they packed up his logbook or some papers. They wrapped them up properly so they wouldn’t get wet or damaged by the weather, so that those who found him would be able to understand exactly what had happened. They probably didn’t leave them on the ground, so probably they covered them with rocks. We heard they buried the captain on a hill—a long narrow hill. So if people were looking in the right place, they would probably find him. If he was a captain, if he was buried properly, there should be signs of something—the ground stirred round, rocks as a marker. We heard they buried the captain carefully. That’s the way we heard it. We heard he was buried on a long narrow hill. The people who went looking for him probably were not looking in the right places.

- No. 15. Elder Jimmy Qirqut of Gjøa Haven on King William Island remembers the stories told about the fascinating missing expedition of Sir John Franklin, and the supposed burial of the Captain. Quoted in Dorothy Harley Eber, Encounters on the Passage: Inuit Meet the Explorers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008. In this Soundcloud recording produced by Elena Baldassarri, the text is read by Ana Shorter.

In September 2014 an expedition led by Parks Canada discovered the wreck of Sir John Franklin HMS Erebus, in the south of Victoria Island in Nunavut. Two years later, in September 2016, the other vessel, the HMS Terror, was found in Terror Bay, further north. The condition of the wrecks seems to prove that Terror and Erebus, trapped in ice off King William Island, were abandoned by the crew who had planned to walk toward the Back River on the Canadian mainland. Unfortunately all of them would die along the way, for a combination of cold, starvation, and disease such as scurvy, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. Most of the bodies were found in King William Island and in Beechey Island. Wrecks and the mournful march of the crew members were recorded by the Inuit in theirs stories.

The Passage Navigated (1903–1984)

The twentieth century opened with a deep faith and confidence in progress and the future. It seemed that all the prodigious scientific discoveries and inventions to be achieved would be for the benefit of mankind.

The geographical explorations reached their peak in this period, although some journeys have since been made to emulate the feats of the great explorers in search of small corners of the world left untouched, either because of their marginal interest in the advanced nations or because they proved too difficult to achieve, as is the case of the Northwest Passage.

Created by the Canadian Government under theOpen Government Licence - Canada.

This work is licensed under the Open Government Licence - Canada.

No. 16. Exploration of the Arctic, 1587–1941. The fourth edition (1974) of the Atlas of Canada contains a map showing exploration routes of the Arctic between 1587 and 1941 for American, British, Canadian, Danish, German, and Norwegian explorers. A 1:7,500,000 scale supplementary map detailing the exploration of Nares Strait accompanies it. Atlas of Canada, Canadian Department of the Interior, 1974.

While the aims were purely scientific in some cases, especially towards creating further knowledge of the world, the desire for personal fame, and often the enhancement of national prestige, was by no means a secondary factor.

This last series of explorations was encouraged by a belief in progress and the ideals of European civilization. While the aims were purely scientific in some cases, especially towards creating further knowledge of the world, the desire for personal fame, and often the enhancement of national prestige, was by no means a secondary factor.

It was a real race between explorers from Nordic countries and those born in other European countries who were not accustomed to the rigors of the polar regions, but who possessed profuse experience of mountaineering.

The first vessel to navigate the Northwest Passage was Roald Amundsen’s ship, the Gjøa, a small 47-tonne boat with a crew of just six men. Amundsen passed across Baffin Bay, through Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait, and reached Beechey Island on 22 August 1903, anchoring in Erebus Bay. From there he followed Franklin’s route towards King William Island, securing for the winter on the eastern coast of the island in a natural harbor, where they established the community of Gjøa Haven. For two winters Amundsen and his crew dedicated themselves to conducting magnetic and meteorological observations, learning Inuit survival skills from the Nattilingmiut who lived there.

The rest of the Maud (1)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The rest of the Maud (2)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The rest of the the Maud (3)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The rest of the the Maud (4)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The rest of the the Maud (5)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The rest of the the Maud (6)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

No. 17. The remains of the the Maud, explorer Roald Amundsen’s schooner, sunk in front of Cambridge Bay. The boat was purchased by the Hudson Bay company for use as a supply and trading ship. Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. August 2013. Photos taken by Enrico Mariotti. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

After Amundsen’s passage until the 1930s, the Canadian government demonstrated interest in the High Arctic, patrolling islands and expressing Canada’s sovereignty with a photographic campaign that documented Northern people and the environment.

Public domain. Photo by George Lancefield, 1906.

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada. Credit: J.-E. Bernier / Library and Archives Canada / C-000744.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

No. 18. Inuit woman and child outside wooden buildings. Skins hanging in background. George Lancefield, “Inuit Woman.” Digital image. Library and Archives Canada, 1906.

The next passage, made by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police vessel St. Roch under the command of Corporal Henry Larsen, did not take place until 1940. It was the first Canadian vessel to sail the Northwest Passage, the first vessel to complete the trip from west to east (1940–42), and the first vessel to make the journey in only one season (1944).

During the Cold War new responsibilities arose in the Arctic areas. US military bases in the region required periodic resupplying, and starting in 1955 Coast Guard vessels were involved in facilitating the construction of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) line of northern radar installations.

In 1957, the delivery of these stations resulted in the first transit of three US Coast Guard cutters: the Storis, Spar, and Bramble. In the same period a new intensive underwater journey using nuclear submarines was initiated. The first transit was registered on 23 July 1958, when the USS Nautilus departed from Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, under top-secret orders to conduct “Operation Sunshine,” the first crossing of the North Pole, where it arrived on 3 August 1958.

After the end of the Cold War, and with temperatures increasing, the Northwest Passage became a traffic route: icebreakers, Coast Guard vessels, research boats, passenger cruises, and cargo ships navigated the passage more frequently every year, leaving the risks, hazards, and perils that made a legend out of this part of the world.