1. The Transnational Education of Petra Kelly

Petra Karin Lehmann was born to Marianne and Richard Lehmann on 29 November 1947 in the provincial town of Günzburg, Bavaria. After her father abandoned the family in 1954, her mother remarried, this time to the US serviceman John Edward Kelly, in 1958. Young Petra also took her stepfather’s last name and became known thereafter as Petra Kelly. Together with her family, Petra Kelly moved to the United States in 1959. She attended high school near US military bases in Columbus, Georgia, and Hampton, Virginia, before earning her BA degree in international relations at American University (AU) in Washington, DC. In 1970, at the age of 22, Kelly returned to Europe in order to study European integration at the University of Amsterdam and then to take up a position at the European Economic Community (the forerunner of the European Union) in Brussels. Kelly had become interested in politics already as a student, but it was during her time in Brussels that she became deeply engaged in antinuclear activism and the peace movement.

Figure 1. A picture of a Bavarian landscape that Petra Kelly drew for her friend Berkley Powell while she attended Hampton High School in Virginia (ca. 1964–1966, exact date unknown).

Figure 1. A picture of a Bavarian landscape that Petra Kelly drew for her friend Berkley Powell while she attended Hampton High School in Virginia (ca. 1964–1966, exact date unknown).

© Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: PKA 3897). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Kelly’s transnational childhood and education profoundly influenced her approach to politics, and indeed her ideas about life in the nuclear age. Living with her family in the southern United States, Kelly was exposed to the nonviolent civil disobedience practiced by participants in the civil rights movement. This influence from her socialization in the United States is visible in her later writings, for example when she repeatedly refers to Henry David Thoreau’s ideas of civil disobedience and Martin Luther King, who for Kelly was “Thoreau in practice.” After moving to Washington, DC, in order to attend American University, she became involved in political life on campus and in the capital city. Already in the spring of her freshman year at AU, she organized the university’s first International Week. The event was intended to foster new discussions within the diverse student body, but Kelly also used it as an opportunity to take up conversations with prominent politicians, whom she invited to campus as part of the event. Acknowledged by the secretary of US Vice President Hubert Humphrey as “a good writer and a very prolific one,” Kelly used her correspondence to build connections to leading US politicians, including Senator Robert Kennedy and Vice President Humphrey. By fall 1968, Kelly was a key student organizer for Humphrey’s presidential campaign. Even amidst her precocious political participation, however, Kelly continued to process her German identity and remained capable of viewing developments in the United States from the perspective of an outsider. In a series of discussions with fellow AU student Abraham Peck, whose parents had survived the Holocaust and fled to the United States, Kelly considered the relationship between Germans and Jews after 1945.

Audio. Abraham Peck remembers Petra Kelly. Excerpts from a public conversation held by historian Belinda Davis with Abraham Peck as part of the conference “Petra Kelly at 75” in the Senate Hall of LMU Munich on 14 October 2022.

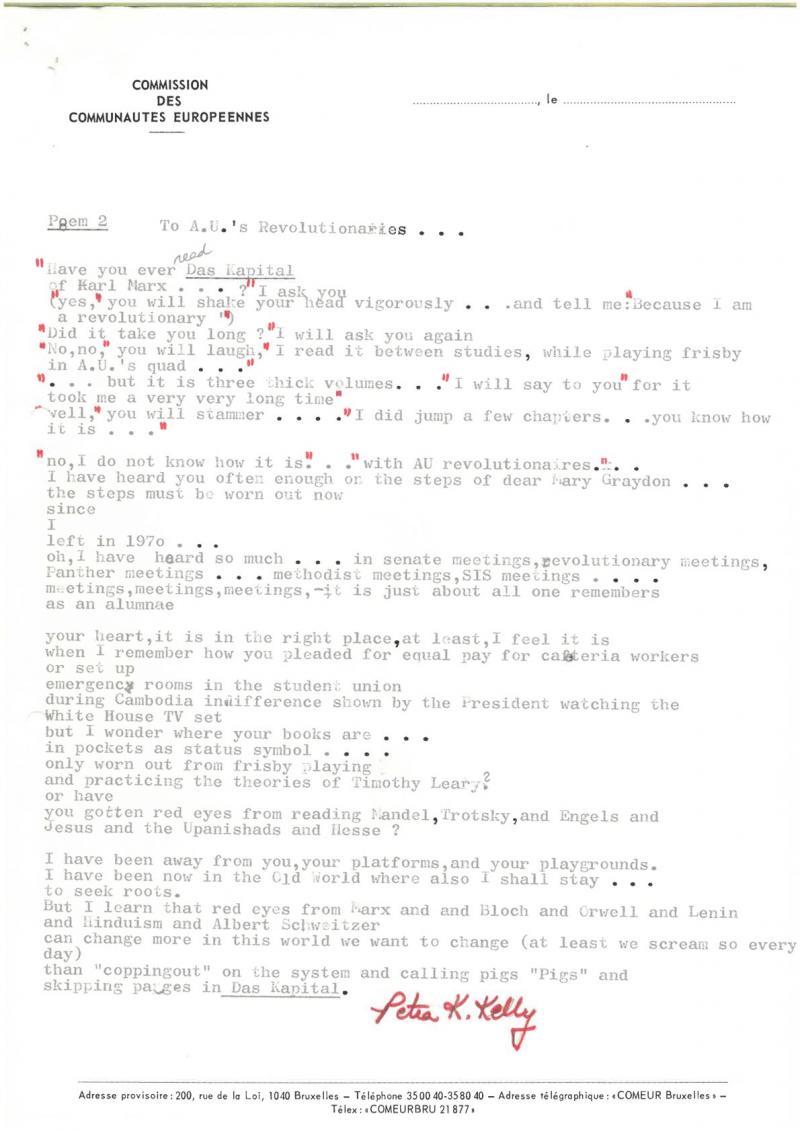

In a poem written in 1972, following her return to Europe, Kelly critiqued “AU’s revolutionaries” for what she perceived as a lack of seriousness and a focus on drugs and frisbee rather than hard work that might change the world.

Figure 2. Poem entitled “To AU’s Revolutionaries.” Petra Kelly wrote this poem in 1972 while she was working at the Economic and Social Committee of the European Economic Community (EEC).

Figure 2. Poem entitled “To AU’s Revolutionaries.” Petra Kelly wrote this poem in 1972 while she was working at the Economic and Social Committee of the European Economic Community (EEC).

© Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: PKA 530,23). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Disappointed not only by student activists but also by the outcome of the 1968 election, when Humphrey lost to Richard Nixon, Kelly decided not to apply for US citizenship and set her sights instead on a return to Europe, where she enrolled in the MA program on European integration at the University of Amsterdam.

And yet, in spite of her disappointment and her move from Washington to Amsterdam in 1970, Kelly’s life and her politics were deeply shaped by her experiences in the United States. In a seminar paper she wrote while at AU, Kelly faulted German 68ers for being too focused on theory and lacking the “love, community [and] human warmth” she had experienced among US student activists. More significantly, her exposure to different styles of activism as well as to electoral politics gave Kelly a fresh perspective on European politics and opened her to alternatives. In short, Kelly’s transnational biography caused her to think beyond borders. It was no coincidence that Kelly decided to study European integration and that she soon sought out a job with the European Economic Community (EEC), the predecessor of the EU, in Brussels. She wanted to work toward the creation of a democratic “United Europe,” with more popular engagement, including direct elections to the European Parliament. Soon after her move to Brussels, Kelly came into contact with German members of the Young European Federalists (known by its French acronym, JEF, for Jeunes Européens Fédéralistes), a group which shared many of her goals.

Figure 3. Martin Luther King, Jr. is arrested for “loitering” in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1958. Kelly, who came to the United States one year later, was inspired by the civil disobedience of Martin Luther King and other activists in the civil rights movement.

Figure 3. Martin Luther King, Jr. is arrested for “loitering” in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1958. Kelly, who came to the United States one year later, was inspired by the civil disobedience of Martin Luther King and other activists in the civil rights movement.

Photo by Charles Moore, 1958. Click here to view source.

.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

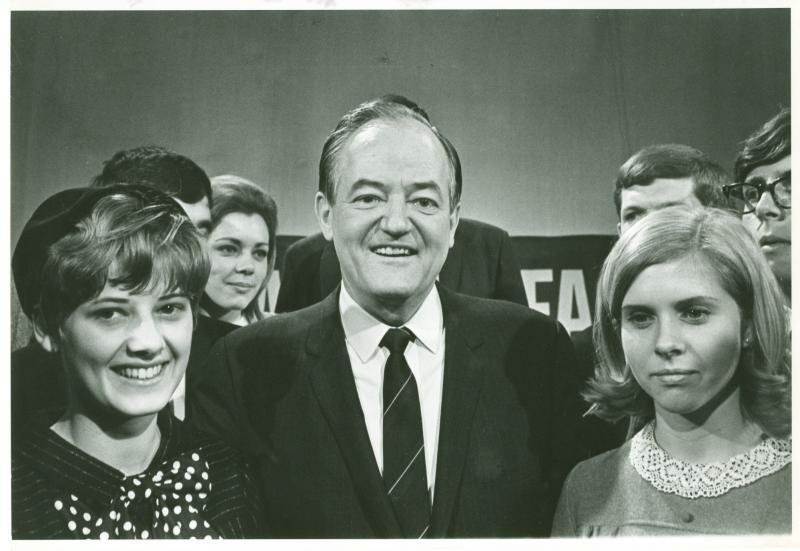

Figure 4. Kelly meets with the Vice President of the United States, Hubert Humphrey.

Figure 4. Kelly meets with the Vice President of the United States, Hubert Humphrey.

Unknown photographer. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-03161-01). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

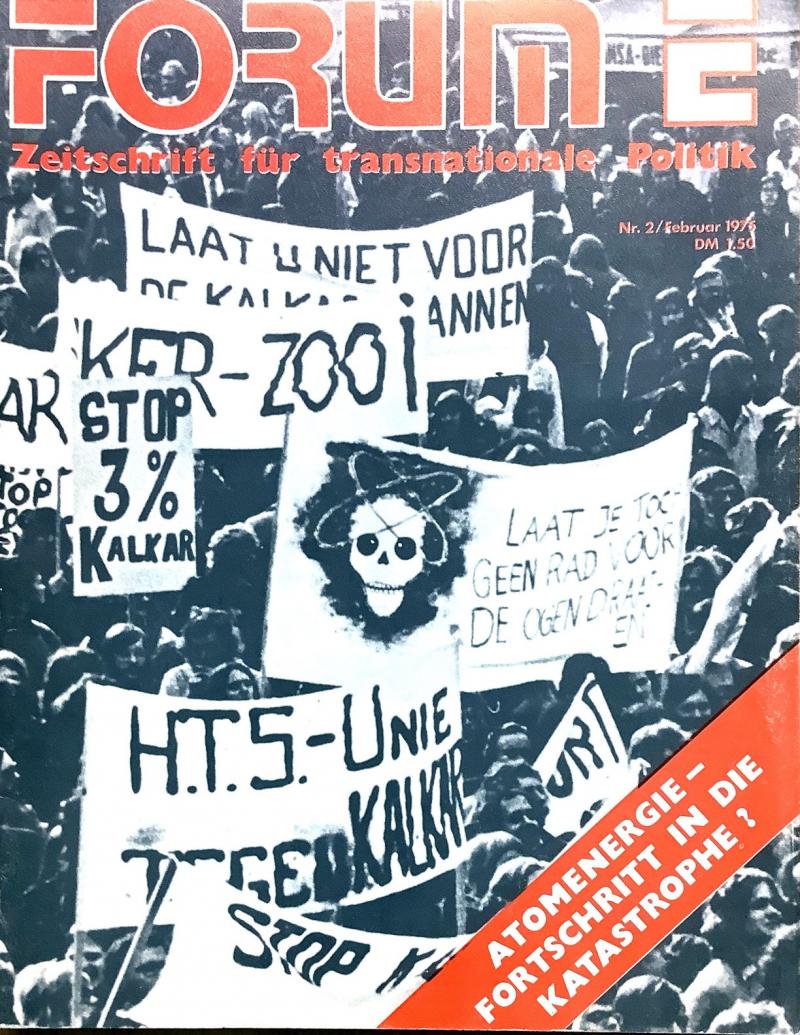

It was together with her contacts in the JEF that Kelly first became engaged in grassroots political action in Europe. The border-crossing movement against nuclear reactors that French, West Germans, and Swiss were collectively building in the Upper Rhine Valley caught the attention of the JEF. The transnational protest movement seemed to be almost a model of the federal Europe to which the JEF activists aspired. Kelly was particularly moved by her experiences in the Upper Rhine Valley, and quickly began promoting the protests among all who would listen as an example of “transnational consciousness” and of highly effective “grassroots resistance.” Having perceived herself as an outsider in Washington, DC, and then in Brussels, Kelly finally felt at home among the grassroots activists who opposed the construction of nuclear power plants near their farms and vineyards in the Upper Rhine Valley. Her transatlantic education had conditioned her reaction to these protests and caused her to see them as a model for her own future political engagement, making crossing borders and alternative approaches key to Kelly’s understanding of green politics.

Figure 5. In February 1975, The Young European Federalists (JEF) released an issue of their Forum E magazine dedicated to the growing struggle against nuclear energy. Petra Kelly played a key role in the creation of this issue, which was widely distributed among grassroots antinuclear groups.

Figure 5. In February 1975, The Young European Federalists (JEF) released an issue of their Forum E magazine dedicated to the growing struggle against nuclear energy. Petra Kelly played a key role in the creation of this issue, which was widely distributed among grassroots antinuclear groups.

© Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (library). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

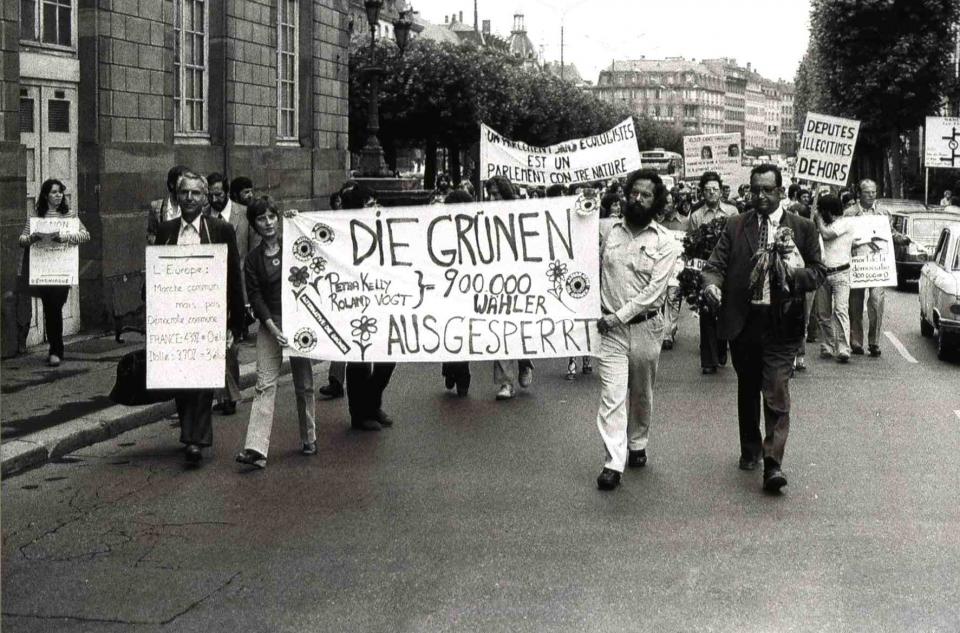

It was for precisely these reasons that Kelly enthusiastically joined the effort to organize an ecological ticket for the first direct elections to the European Parliament in 1979. Kelly helped to found what became known as the Alternative Political Association: The Greens (Sonstige Politische Vereinigung: (SPV)-Die Grünen) and then served as the group’s lead candidate in the 1979 election. In this role, she proposed that she would “speak up for a decentralized, non/nuclear, non/military [sic], and gentle Europe—a Europe of the Regions and of the People.” She understood the alternative political association as part of a wider effort to “build Europe from BELOW and not from ABOVE.” The list that Kelly led received more than nine hundred thousand votes in the June 1979 election. Unfortunately, this amounted to only 3.2 percent of the vote, not enough to jump German electoral law’s “5 percent hurdle” and qualify for seats in the European Parliament. On the day of the parliament’s constitutive session in Strasbourg, Kelly and other Greens marched through the streets in protest. After unfurling a protest banner from their seats in the parliament’s spectator gallery, however, the Greens were ejected from the building. Though no green candidates were seated in the European Parliament in 1979, the election campaign presaged the formation of Die Grünen in 1980. Kelly’s European and transnational perspectives, and her experience campaigning for the European Parliament, motivated her to participate in this process and to serve as the Greens’ lead candidate in their first two campaigns for seats in the West German Bundestag, to which she—and 27 other Greens—were finally elected in 1983. Hence, Kelly’s claim that “the need to act transnationally, European, and also internationally as a Green must never be forgotten” was an honest assessment of her own understanding of the new party’s transnational origins and a reflection of her transatlantic education.

Figure 6. Green candidates, including Petra Kelly, march through the streets of Strasbourg, France, on 17 July 1979, the date of the constitutive session of the first directly elected European Parliament. The banner, carried by candidates Petra Kelly and Roland Vogt, reads “Die Grünen, 900,000 votes, shut out!”

Figure 6. Green candidates, including Petra Kelly, march through the streets of Strasbourg, France, on 17 July 1979, the date of the constitutive session of the first directly elected European Parliament. The banner, carried by candidates Petra Kelly and Roland Vogt, reads “Die Grünen, 900,000 votes, shut out!”

Unknown photographer, 1979. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-01700-02). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.