6. Petra Kelly’s Legacy

Petra Kelly has been remembered in many different contexts and for a variety of reasons since her life was suddenly and violently ended in 1992. The spectrum ranges from the remembrance of Kelly’s concrete political work to media speculation about the circumstances under which she was killed, which, particularly in Germany, arises almost every October on the anniversary of her death. Even decades after the heyday of her activism in the 1980s, Petra Kelly has not been forgotten in many parts of the world. The different ways that her legacy has been interpreted in Germany and abroad reflect her alternative, transnational approach to politics.

Figure 1. Die Grünen held a joint memorial service for Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian on 31 October 1992 at the Beethoven Halle in Bonn.

Figure 1. Die Grünen held a joint memorial service for Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian on 31 October 1992 at the Beethoven Halle in Bonn.

Photo by Hermann J. Knippertz, 1992. © Hermann J Knippertz / AP Images. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

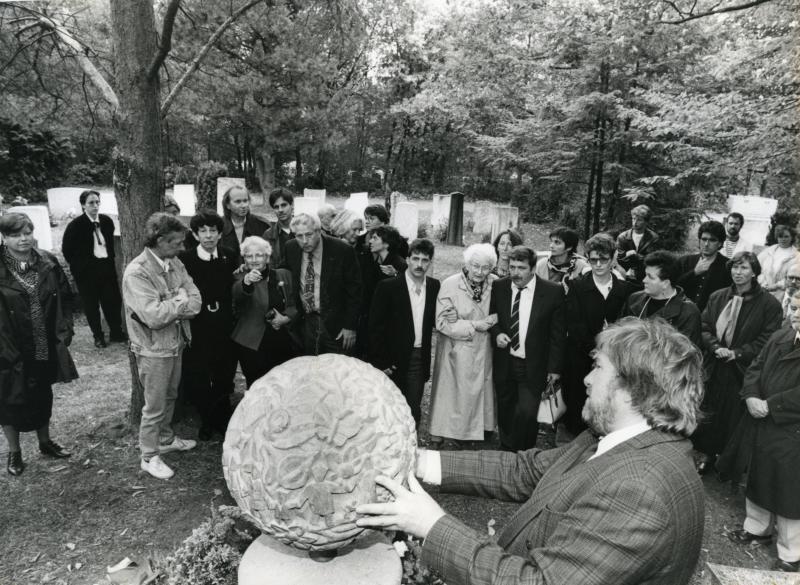

Figure 2. A memorial service at Petra Kelly’s gravesite in Würzburg, Germany, on the first anniversary of her death, 1 October 1993. Those in attendance include Petra Kelly’s mother and stepfather, her grandmother, and Green party politicians from Germany and the United Kingdom.

Figure 2. A memorial service at Petra Kelly’s gravesite in Würzburg, Germany, on the first anniversary of her death, 1 October 1993. Those in attendance include Petra Kelly’s mother and stepfather, her grandmother, and Green party politicians from Germany and the United Kingdom.

Unknown photographer. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis. (signature: FO-05625-08). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

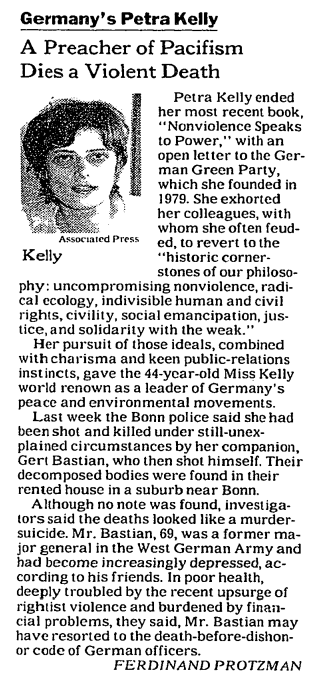

The unclear circumstances of Kelly’s death overshadowed her legacy, especially in Germany. In October 1992, Kelly was shot in her sleep by her partner Gert Bastian, who then killed himself. The bodies lay undiscovered in the couple’s Bonn home for weeks. Unsure how to react and initially unwilling to come to terms with the idea that Bastian had murdered Kelly, Die Grünen held a joint memorial service for the pair. Indeed, in early 1993, the public prosecutor’s office certified the deaths as a “double suicide,” a decision that tarnished Kelly’s image as an icon of peace and nonviolence. Over time, however, the interpretation prevailed that Kelly had certainly not intended to end her life at the barrel of a gun. Some circumstances surrounding her death remain unclear even after three decades. However, the known facts of the case strongly support the conclusion that Bastian’s shooting of Kelly was a case of femicide. The feminist and publisher of Emma magazine, Alice Schwarzer, who discussed the relationship between Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian in depth in her 1993 book Eine tödliche Liebe (A fatal love), played a major role in this reinterpretation of the violent end to Kelly’s life.

Figure 3. A New York Times article published shortly after Peter Kelly’s death was reported. A version of this article appeared in print on 25 October 1992, section 4, page 2 of the national edition with the headline: 18–24 Oct: “Germany’s Petra Kelly: A Preacher of Pacifism Dies a Violent Death.”

Figure 3. A New York Times article published shortly after Peter Kelly’s death was reported. A version of this article appeared in print on 25 October 1992, section 4, page 2 of the national edition with the headline: 18–24 Oct: “Germany’s Petra Kelly: A Preacher of Pacifism Dies a Violent Death.”

© 1992 The New York Times Company. All rights reserved.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

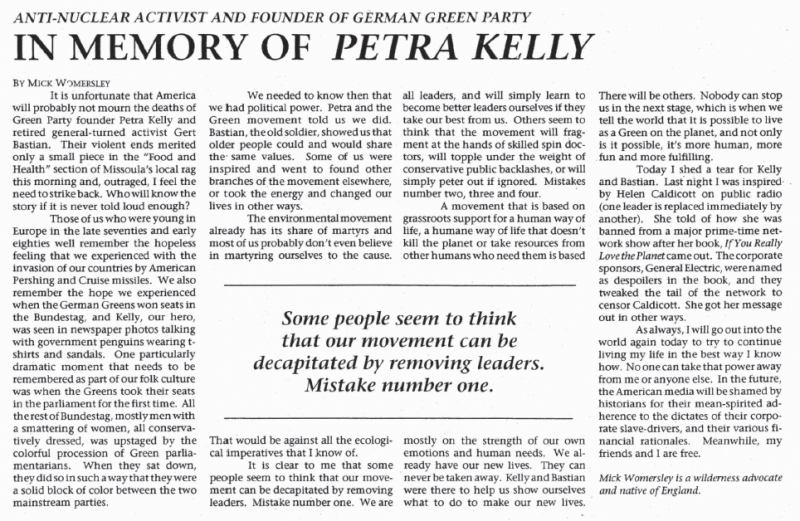

Figure 4. An obituary for Petra Kelly was published in the journal of the US radical environmental group Earth First!. Roselle, Mike, ed., Earth First! Journal 13, no. 1 (2 November 1992).

Figure 4. An obituary for Petra Kelly was published in the journal of the US radical environmental group Earth First!. Roselle, Mike, ed., Earth First! Journal 13, no. 1 (2 November 1992).

© 1992. Republished by the Environment & Society Portal, Multimedia Library. The user may download, preserve and print this material only for private, research or nonprofit educational purposes. The user may not alter, transform, or build upon this material.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

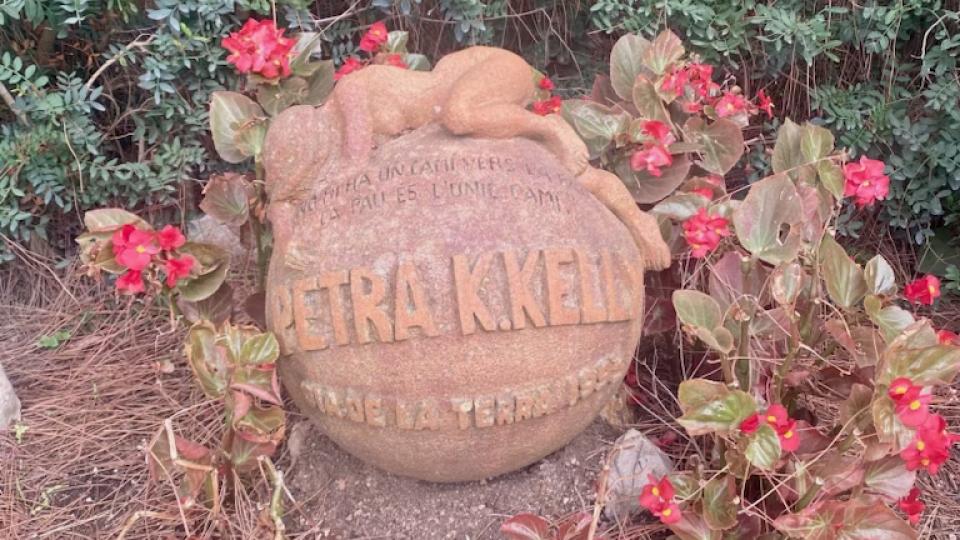

Even as Kelly’s death was still being discussed, her life and her many achievements began to make their way into public memory. Indeed, outside of Germany, Kelly’s life and her many contributions quickly overshadowed the debate about the circumstances of her death. Already on 25 April 1993, a memorial was dedicated to Petra Kelly in Spain. In the aftermath of Earth Day, the Catalan city of Barcelona decided to name a garden on the slope of the Montjuïc hill after Petra Kelly (Jardí Petra Kelly), in which a small sculpture was also placed in her honor. Even in Germany, Kelly’s life has been celebrated with public monuments. On the first anniversary of Kelly’s death, an elaborate gravestone was unveiled in Würzburg’s Waldfriedhof, the same place where her half sister Grace P. Kelly was buried and where her grandmother Kunigunde Birle was later entombed. Streets and squares in many German cities have been named after Petra Kelly since the 1990s, most notably in the former capital city of Bonn, where Kelly served for seven years as a member of parliament.

After the mourning and these initial commemoration ceremonies had been held and Petra Kelly’s papers had been safely stored in the newly founded Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (Green Memory Archive), however, German discussions of her legacy quieted down. Her political positions, from her uncompromising commitment to nonviolence to her criticism of possible government participation by the Greens, were no longer majority opinions within her own party by the end of the 1990s. In 1998, Die Grünen, now united with the East German group Bündnis 90 (Alliance 90), entered into government as junior coalition partners to the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). The following year, in 1999, the majority of the delegates to a Die Grünen party convention voted in favor of NATO’s engagement in the Kosovo War. It was only after the end of the Red-Green coalition in 2005, when the Greens needed to regroup in opposition, that the idealism of a thinker like Petra Kelly could once again be found more widely within Die Grünen. This was probably one of the reasons why Ralf Fücks, then president of the Heinrich Böll Foundation (affiliated with Die Grünen), wrote in 2007 in an illustrated book published by the foundation on the occasion of Petra Kelly’s 60th birthday of a Wiederannäherung (rapprochement) between Kelly and the Greens. Nonetheless, the party’s relationship to the memory of its erstwhile figurehead remained tenuous in the following years.

Figure 6. Petra Kelly’s mother, her stepfather, and the Green politician Renate Künast stand by the sign for “Petra Kelly Allee” in Bonn in August 2006.

Figure 6. Petra Kelly’s mother, her stepfather, and the Green politician Renate Künast stand by the sign for “Petra Kelly Allee” in Bonn in August 2006.

Photo by Federico Gambarini. © picture-alliance/ dpa | Federico Gambarini. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

More recently, however, Kelly’s name has been invoked with greater frequency. In Germany, interest in the circumstances of her death was reinvigorated by true-crime podcasts and television series. The contrast between Kelly’s relentless political engagement and her sudden death was a major subject of Torsten Körner’s 2021 film Die Unbeugsamen (translated into English as Femocracy), which focused on women’s struggles to enter and transform the hypermasculine world of West German parliamentary politics.

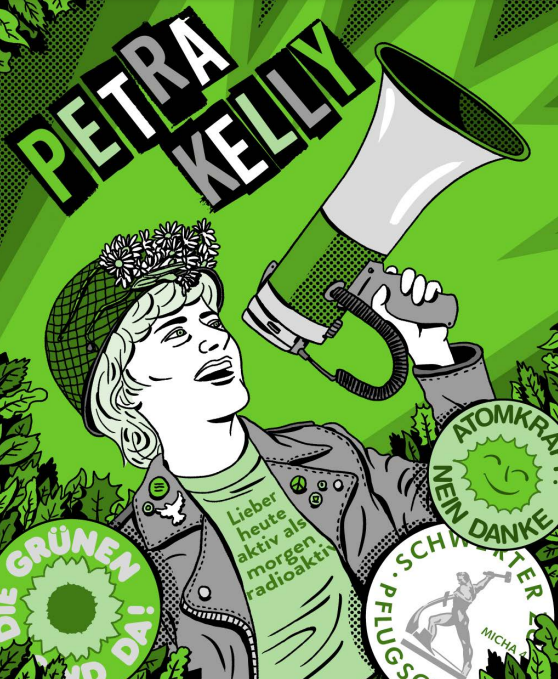

At the same time, the ongoing climate crisis made Kelly’s approach to politics seem increasingly relevant. Her emphasis on the importance of Indigenous knowledge and the need to stand with “native peoples” who are “suffering from the expansion of Western society and Western ways of life” rings true in our era of global environmental destruction and growing militarism. Likewise, her call to “transform consumer mentality and our industrial economic growth system into an ecological sustainable economy with conservation replacing consumption as the driving force” is all the more urgent in the climate-change era. Works in a variety of media offered new ways of thinking about Kelly’s legacy. In September 2020, the Canadian novelist Shaena Lambert published a work of historical fiction that explored Kelly’s relationship with Gert Bastian, and imagined Kelly as her closest political comrades saw her. By emphasizing the importance of Kelly’s relationships, Lambert offered a new means of reflecting on Kelly’s understanding of Green politics and their meaning in the present. In 2022, the German author and illustrator Simon Schwartz published a visually stimulating graphic novel that linked Kelly’s radical views and political visions with the bold acts of protest and civil disobedience that underpinned them.

Figure 7. Simon Schwartz created a graphic novel about the life of Petra Kelly, which was published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation on the 75th anniversary of Kelly’s birth in 2022.

Figure 7. Simon Schwartz created a graphic novel about the life of Petra Kelly, which was published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation on the 75th anniversary of Kelly’s birth in 2022.

Published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation. Used by permission. Illustration, text, and typesetting by Simon Schwartz, Hamburg.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Following the brutal Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Kelly’s important role as a leader and spokesperson of the 1980s “new peace movement” came back into focus, as well. On account of Kelly’s total rejection of violence, her name was regularly invoked as a symbol of Germany’s post-1945 antimilitarism and the Green Party’s pacifist roots. Her positions were contrasted frequently with contemporary Green politicians’ support for shipping arms to Ukraine and increasing Germany’s domestic defense budget. In contrast to the 1999 debate over the Kosovo War, almost no one in or around Die Grünen emphasized nonviolence as the guiding principle in the debate over how Germany ought to respond to the Russian invasion.

By the fall of 2022, on the 75th anniversary of her birth, the significance of Petra Kelly’s life and her political work had become widely acknowledged in many parts of the world. Strikingly, however, there remained important differences in the way she was remembered in Germany and elsewhere. Within Germany, Kelly was still criticized for shortcomings in her work within Die Grünen; the extent to which her particular approach to politics shaped the party and defined its image continued to be overlooked. Perhaps more significantly still, her central role in building political networks and green parties around the world was rarely mentioned.

Figure 8. A protester holds a sign reading “What would Petra Kelly say?” at a protest for heat, bread, and peace on 5 September 2022 in Berlin.

Figure 8. A protester holds a sign reading “What would Petra Kelly say?” at a protest for heat, bread, and peace on 5 September 2022 in Berlin.

© 2022 Florian Boillot. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In other countries, however the picture was quite different. Emphasis on Kelly’s global networking and her role in aiding grassroots movements and popularizing green politics in many different counties is widely acknowledged in places like Spain, Italy, and the United States to name just a few examples. Hence, one of Kelly’s closest colleagues, the activist Eva Quistorp, recently remembered Kelly’s importance for the development of Die Grünen, but also emphasized the extent to which Kelly’s legacy was a transnational one that had to be understood beyond the boundaries and frameworks of traditional, national politics. In an October 2022 open letter addressed to her deceased friend, Quistorp wrote, “your accomplishments should remind us of the strength and the vision of all those who struggle now, everyday and without acknowledgement, for solidarity and democratic change.”

“Missing you!”—A personal letter

Dear Petra,

I am not the only one who is missing you very much, you are missed by many in this country and around the world. Especially now, when Putin’s power apparatus is waging a brutal war against Ukraine. You are also missed by Russian feminists, who dare to take non-violent actions against the war of Putin’s mafia.

Petra, your name, like Peter, reminds us of a rock: you were a rock on which the anti-nuclear weapons movement and the Greens were built throughout Europe. You were part of the awakening in the U.S. in the 1960s with the civil rights movement—which, with Martin Luther King, was also a peace movement against the power of the military-industrial complex and against the Vietnam War, which we protested in West Berlin and you protested in the U.S. with Robert Kennedy.

You held great speeches at the peace demonstrations in the 1980s in Bonn that I helped organize with the “Women for Peace.” Unfortunately, neither Georg Mascolo quotes you in his good articles in the South German Newspaper (Süddeutsche Zeitung) on nuclear weapons, nor Green foreign minister Annalena Baerbock in her UN speeches. You supported the women’s peace movement worldwide and, together with me, the women for peace in the GDR.

You are missed by many now, when we must insist in the UN on the implementation of Resolution 1325, which since 2000 has advocated the participation of women at all levels in peace negotiations. You did not live to see the founding of the women’s rights organization medica mondiale in Cologne in 1993, in which I participated as an MEP. Unfortunately. Since you also so wanted to help practically against the traumas of women and children in wars and terror.

Do you remember when we were together at the World Women’s Conference in Moscow in June 1987—and with Helen Caldicott, our third-in-command since the anti-nuclear conference in Dublin, where we had met in 1978, daring to raise the health dangers of Chernobyl? The Soviet Women’s Federation allowed us to speak openly back then under Glasnost and Perestroika! What a contrast to the ban on the human rights organisation Memorial and the newspaper Nova Gazeta today. They—I’m sure you were happy to hear on your cloud—won the Nobel Peace Prize, along with oppositionists from Belarus and civil society in Ukraine.

You would have come to the vigils at the Brandenburg Gate for the Green Movement in Iran in 2009, which I helped organize. Also now you would have been there when Duezen Tükkal organized a demo for the women in Iran protesting against compulsary hijab and against the reactionary Islam theocracy and the corrupt elites in Iran and their murders and lies. You always wanted both: nuclear disarmament and full women’s rights. You were no stranger to criticism of religion as a liberal Catholic.

Myself, and many others, also miss you in the feminist debates of today on prostitution, hijabs for teachers, diversity, anti-discrimination and quotas. You clapped immediately when I was the first in Germany to call for a women’s quota at the founding party conference of the Green Party in my speech in Karlsruhe in January 1980. After that, we pushed it through in the first committees—long before the Greens’ women’s statute of 1986. We both talked about forced marriage and genital mutilation and women’s poverty, in conjunction with U.S. and French feminists.

We both invented the sunflower as the logo of the Greens with Roland Vogt, who was one of the trio of founders from the Federal Association of Citizens’ Initiatives for Environmental Protection (BBU) and the Young European Federalists (JeF). And we then gave the sunflower to the Greens as a gift. It wasn’t Josef Beuys, as a German Television (ZDF) film claimed the other day at the Green Party convention, along the lines that only famous men can invent famous logos and names. No. It was our trio, who—like tens of thousands of anti-nuclear activists—knew the logo of the designer from Denmark: “Atomkraft, nein danke!” (“Nuclear power, no thanks!”).

We suggested the name “The Greens” as if from the same mouth when Milan Horacek of Charter 77 told us that the left-wing party founding scene wanted to call themselves “The Alternative”. This reminded us of Rudolf Bahro’s important book against environmental destruction, but was too abstract for us. We felt the name “The Greens” was more sensual and related to spiritual traditions of hope. The Greens should have been more respectful of this gift from three party founders.

Instead, for the past 30 years, you have been almost forgotten in official speeches and media appearances by top Greens. And now you are rather used as an ornament, as it happens to many dead people who experienced competition and envy and intrigue during their lifetime. No quote from you and not even your name was mentioned at the big celebration of “40 years Greens” in early January 2020. Not even from Lukas Beckmann, who was the only founding Green to speak—along with Ströbele, Steinmeier and Luisa Neubauer, Annalena Baerbock, Robert Habeck.

And eight years earlier, at the funeral service in 1992, you and your murderer were remembered at the same time. I found that just as bad then as the silence in 2020. Later in the evening of the green anniversary celebration, slightly tipsy, I met Ina Deter, who hugged me in tears and called out “Eva, where is Petra? Why is no one talking about Petra?” This was overheard by a journalist of the weekly ZEIT (Time), but she probably couldn’t relate anymore to us two feminists from the era of the great peace movement and the founding period of the Greens.

What actions do you think you would have done in the last 30 years if you hadn’t gotten sick ? Something like the one at Alexanderplatz against the repression in the GDR or the one at the embassy in South Africa against the apartheid system ? Surely you would have been there at the climate demonstrations. Although you would have spoken out clearly for non-violence—as we did together in the 1980s. You would have made radical speeches, but you would have opposed extreme actions.

You were actually a Greta of your time. You also struck apocalyptic tones from time to time and scolded on politics. Yes, even on the Greens, which you wanted to be an anti-party. You also got a lot of shitstorms back then and mean letters—there was no Twitter yet—from right-wing extremist milieu with the mail.

You didn’t want to rotate and give up your seat in parliament. But you wouldn’t have necessarily wanted more than eight years in the Bundestag either, which is normal for many Greens today. You wanted to go to a university in the U.S.A., you told me a few days before your murder, enthusiastically and full of life. You were unhappy with the Green Heinrich-Boell Foundation and the Green Party at the time, feeling abandoned and forgotten with your money troubles and with what you could contribute to the Greens.

But it was not you, but your life partner Gerd Bastian who seemed depressed at the conferences in Salzburg and Berlin in September 1992, your last month of life, and aged since his accident. I always tried to perceive you as Petra, as a unique female personality, and believed in us as a feminist tandem as in the beginning. I was never entirely comfortable with this “General for Peace.” Nor with his organization, in which some from Italy and Holland were close to the SED, if not the USSR and the KGB.

It is strange that he shot you in your sleep after you had been briefly with the Stasi authorities in Berlin in September, as you told me. Your all-too-early death, your murder by your life partner remains a great mystery. It was a shock for me that burdened me for years. I would have gladly redeemed you from this entangled relationship.

At the World Women’s Conference in Miami in 1991, we were happily together again for a short time. Bella Abzug and Mim Kelber, two great female figures in U.S. peace and women’s politics invited on a ship where we could finally eat and talk together without the General for once. The results of this conference in Miami, which we summarized with Bella and Claire Greensfelder in Women’s Agenda 21, should be taken to heart by the Greens of today.

To the new climate movement, let it be said that we were already talking about climate in 1978, and Petra was one of their predecessors. That as a former Social Democrat and former EU administrator, facts and administrative knowledge was as important to her as it is to Scientists For Future today. Would the talk shows of today have invited you? And how you would have fared? You failed on Sat 1-TV back then. Many women of the old women’s, environmental and peace movement never got on TV.

That we would appear in articles in the established media was unthinkable at the time. But you desperately wanted to conquer parliaments besides the media and parties. You aspired to greatness, perhaps sometimes too strained and too pathetic. You were not grounded enough by those who surrounded you after 1983 and profited from you in the parliament, the Bundestag. And competed with you or intrigued in the party against you.

I was always more of a “down-to-earth” and undogmatic “Sponti” leftist of West Berlin than you, in whom the amazon and the courageous suffragettes of the past continued to tick. Black Lives Matter was familiar to us through the Black Power movement and Nelson Mandela. Plus your 1987 Tibet hearing and your friendship with the Dalai Lama—to whom you introduced me, and laughed when I dared to present him with a rose.

How do you think you would have fared with Angela Merkel? You would have had to change your speeches a lot if you were now facing the questions of the turn of the times like us. As a democrat who was not in favor of leaving Nato like many Greens, but like me always in favor of Nato reforms, you would not have been against arms deliveries to Ukraine in principle.

You blocked nuclear weapons transports together with Heinrich Boell and his wife in Mutlangen in Southwest Germany—non-violently in the spirit of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. You were unique with your charisma. You drew me and many others into the stream of hope and parliamentary politics. Like us, however, you also had weaknesses and dark sides.

Petra, today you would be the age of the “climate women seniors” from Switzerland who, together with Greenpeace, are suing the inaction of governments before the European Court of Human Rights. Would you go with them? Today with the protection against right-wing and media hostility that you lacked 30 years ago. And which you then unfortunately sought from a general. I wonder if you would enjoy the book and podcasts now being produced by the Boell Foundation to mark the 30th anniversary of your death and the 75th anniversary of your birth.

At any rate, it’s good that some of your speeches are being reread, the Petra Kelly Archive is being used for the present—and you’re not being digested in movies with the mysterious “relationship thriller” ending. You have been spared the wars of the present and the right wing party Alternative for Germany (AfD) as well as the dictatorships of today that threaten freedom of the press and democratic welfare states. Also Big Tech with its global corporate power. You would certainly have sued Facebook.

Joan Baez “We Shall Overcome”—will still please you with her songs. And she won’t forget you. Hopefully, neither will the many feminist climate activists and young parliamentarians from Europe and Africa and Latin America and Asia.

Eva Quistorp, Berlin, 12 October 2022

Petra Kelly’s longtime political comrade, Eva Quistorp, wrote this letter to her on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of her birth in 2022. Original German text © 2022 Eva Quistorp. English translation © 2022 Rebecca Hillauer, https://hillauer.substack.com/p/today-petra-kelly-would-have-turned. Used by permission.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter