2. Transnational Women’s Networks: Petra Kelly and her Global Alliance of Friends and Companions

Petra Kelly—still a prominent figure today—stands for an almost unrestricted struggle for environmental protection, peace, and human rights. But she was by no means the only one. She was part of a global movement in which numerous women committed to, connected with, and supported each other. This chapter takes a closer look at Petra Kelly’s transnational connections and her companions across the world.

Figure 1. Petra Kelly and her “green” companions and friends at the first European meeting of the Green Party in Stockholm 1987. From left to right: Freda Meissner-Blau (Austria), Petra Kelly (Germany), Solange Fernex (France), Sara Parkin (Great Britain).

Figure 1. Petra Kelly and her “green” companions and friends at the first European meeting of the Green Party in Stockholm 1987. From left to right: Freda Meissner-Blau (Austria), Petra Kelly (Germany), Solange Fernex (France), Sara Parkin (Great Britain).

Unknown photographer, 1987. © Private archive Freda Meissner-Blau. Published in: Freda Meissner-Blau, Die Frage bleibt (Vienna: Amalthea Verlag, 2014). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The environmental movement emerged in the early 1970s from the anti-nuclear, women’s, and peace movements. At that time, I was already friends with Petra Kelly, the founder of the German Green Party, and Sara Parkin, the founder of the English Green Party. We were three women . . . who met even before the parties were founded.

—Freda Meissner-Blau in 2007

Freda Meissner-Blau (1927–2015) was not only a doyenne of the Austrian environmental movement and cofounder of the Green Party in Austria but also a friend and fellow campaigner of Petra Kelly (1947–1992). The women in figure 1 were pioneers of the green movement, activists, and politicians. They were friends and companions in their struggle for peace, environmental protection, human rights, and the women’s movement. Thus, they could establish transnational communication systems and gain strength for their causes.

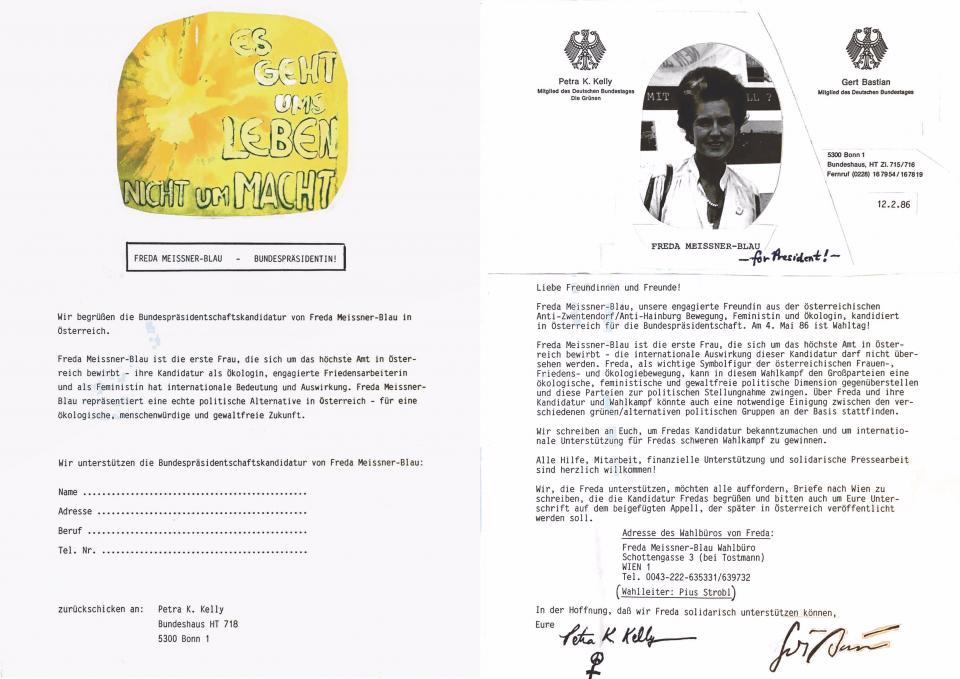

Figure 2. A call by Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian to support the election of Freda Meissner-Blau as federal president in Austria in 1986. Supporters were asked to write letters to Vienna, and signatures were collected.

Figure 2. A call by Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian to support the election of Freda Meissner-Blau as federal president in Austria in 1986. Supporters were asked to write letters to Vienna, and signatures were collected.

© Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: PKA, 1928). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

When Meissner-Blau ran for the federal presidency in Austria in 1986, Kelly activated her international contacts and wrote, together with Gert Bastian (1923–1992), an appeal for support: “Freda Meissner-Blau for president!” In it, Kelly affirmed:

Freda Meissner-Blau is the first woman to run for the highest office in Austria—the international impact of this candidacy should not be overlooked. As an important symbolic figure of the Austrian women’s, peace, and ecology movements, Freda can confront the major parties with an ecological, feminist, and non-violent political dimension in this election campaign and force these parties to take a political stand.

Kelly was well aware of the cross-border implications of such a national election. Although her Austrian companion did not win the election against Kurt Waldheim (1918–2007), the transnational support network was helpful and relevant for further concerns. Mutual support in political as well as personal matters was continuously maintained.

Figure 3. Group discussion with Petra Kelly in the Rotstilzchen pub in Vienna in 1980. Kelly travelled across Austria for a lecture tour. She described it as a journey full of new hope.

Figure 3. Group discussion with Petra Kelly in the Rotstilzchen pub in Vienna in 1980. Kelly travelled across Austria for a lecture tour. She described it as a journey full of new hope.

Unknown photographer, 1980. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-01561-01). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Neighboring Austria was particularly central to cross-border communication and networking for the German environmental movement, which also had its traditions in German and Austrian nature conservation. This included, for example, collaborations within and between the two Alpine associations and national parks, as well as the transfer of ideas.

The successful resistance against the nuclear power plant in Zwentendorf (1978) and against a power plant in Hainburg (1984), which became symbolic and formative for Austrian identity, must be considered in the specific regional, national, and transnational context of the new social movements at the time. Especially in border areas like the Bavarian-Austrian one, the resistance against nuclear power (e.g., Wackersdorf), whose damage does not stop at national borders, played a transterritorial role.

Petra Kelly was also committed to spreading her messages in Austria, maintaining many personal and professional contacts, and giving public lectures. For a lot of people in the Austrian environmental movement, she served as a role model. In 1980, Kelly called for cross-border activism: “I mean, we now also have a common task: to help our Austrian friends—be it through the financial support of the anti-Zwentendorf movement, be it with moral help through letters and telegrams, or be it just about a forthcoming joint action.” In this regard, feminist values and women’s bonds were central elements for her.

The same applied to her efforts for peace in the GDR (East Germany) and her contacts there—for example, with the East German opposition figure and peace activist Bärbel Bohley (1945–2010), with whom she maintained an amicable as well as interest-driven relationship across the border.

Figure 4. World Women’s Congress for a Healthy Planet, Miami, 1991. From left to right: Eva Quistorp, Vandana Shiva, Petra Kelly, Mira Shiva.

Figure 4. World Women’s Congress for a Healthy Planet, Miami, 1991. From left to right: Eva Quistorp, Vandana Shiva, Petra Kelly, Mira Shiva.

Unknown photographer, 1991. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-03762-01-cp). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Figure 5. World Women’s Congress for a Healthy Planet, 1991, Miami. From left to right: Petra Kelly, Bella Abzug, Eva Quistorp.

Figure 5. World Women’s Congress for a Healthy Planet, 1991, Miami. From left to right: Petra Kelly, Bella Abzug, Eva Quistorp.

Unknown photographer, 1991. © Eva Quistorp ( A-Quistorp, Eva, in: AGG, signature: FO-03762-02-cp). Courtesy of Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Many different approaches could be united under the umbrella of the environmental movement. On the one hand, this created potential for conflict and ambiguity of goals; on the other hand, it enabled global networks or communication systems and a transfer of ideas that would otherwise hardly have been possible. In her holistic understanding of the environment, which included peace, women’s, and human rights, Petra Kelly found contact points with women from the most diverse spaces and worlds of ideas. The fact that women, in particular, could create new spaces and contacts in this diverse setting is not only obvious but relevant for characterizing environmentalism. Ecofeminist ideas managed to link some of the strands by emphasizing the suppression of women, social inequality in the patriarchy, and the exploitation and subjugation of nature. Eva Quistorp (*1945), cofounder of Die Grünen and one of the central figures of the ecology, peace, and women’s movements, was one of the first women in Germany to talk publicly about ecofeminism, pointing out the degradation and objectification of women. And she was one of Kelly’s crucial contacts.

Audio. Speech by Petra Kelly at the National Organization for Women (NOW) convention in San Francisco, 1990. Kelly talks about the importance and connections between women’s movements and the environment. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: PKA, 3632, TK-A-PKE-0138). Used by permission.

At international meetings, the most diverse, even opposing, ideas came together. Even though not everything went smoothly, and the women’s movement disagreed and fragmented on many points, these meetings and women’s networks formed a strong global bond and were a center for transnational transfers of ideas. International meetings and contacts, such as those with Indian activist Vandana Shiva (*1952), were undoubtedly motivated by women’s solidarity and the fight against patriarchy. Petra Kelly was well aware of the clout of such connections.

Figure 6. The logos of the World Union for the Protection of Life and the Collegium Humanum, institutions that brought together fundamentally different people, including those with right-wing ideas.

Figure 6. The logos of the World Union for the Protection of Life and the Collegium Humanum, institutions that brought together fundamentally different people, including those with right-wing ideas.

© Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: PKA, 1920). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Within the chameleonic framework of environmentalism, the most diverse motives could come together. The ambivalence of such a heterogeneous movement can be illustrated by problematic contacts such as that between Kelly and the right-wing extremist Ursula Haverbeck-Wetzel (*1928). In this respect, the World Union for the Protection of Life (Weltbund zum Schutz des Lebens, or WSL), founded in 1960 in Salzburg, Austria, and the Collegium Humanum, which was headed by the Haverbeck couple, served as rallying points. These institutions were a link between the environmental movement and the far right, between culturally pessimistic conservatism and biologistic right-wingers, united in protest against nuclear technology. Organizations such as the WSL certainly had a unifying and networking value for the most disparate people, ideas, and motivations. Kelly was a frequent guest and speaker at WSL events. In April 1979, for example, Haverbeck and Kelly organized a seminar on “Women and family in the constraints of the environment. Can women make a special contribution to ‘Lebensschutz’ [protection of life]?”

Kelly was deeply opposed to right-wing ideas and was aware of the dangers of right-wing tendencies infiltrating environmentalism—she corresponded with Freda about this. However, the incorporating, idealistic view of the need to protect a shared environment functioned as a connector. In the case of personal contacts, several factors, such as sympathy or opportunism, can also play a role. Either way, a comprehensive historical understanding of environmentalism requires consideration of all identifiable contacts and networks, including the problematic ones. This allows for a more differentiated view of history and helps us to fathom insights relevant to the present: who engages in activism, why, and with whom.