Introduction

No. 1. The Northwest Passage. Myth, Environment, and Resources. Introduction. Video by Elena Baldassarri. Interviews with Franklyn Griffiths, Joe and Susie Koaha, Adam Lajeunesse, Timothy Leduc, and Susie Maniyogina. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The Northwest Passage is a sea corridor connecting the Atlantic and Pacific through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and along the northern coast of North America. It consists of a series of deep channels from the north of Baffin Island to the Beaufort Sea, with a total length of around 1,500 kilometers in length. It does not consist of one single passageway, but rather a number of alternative routes.

European explorers searched for the passage for 300 years with the aim of finding a commercially viable westward sea route between Europe and Asia. It was finally traversed successfully by Roald Amundsen between 1903 and 1906, but it proved impractical as a regular shipping route.

Even today, it continues to be one of the most difficult maritime routes due its position north of the Arctic Circle and because it requires a hazardous voyage through wind and giant icebergs drifting south, posing a serious hazard to shipping in winter and in summer. The dense ice prevents commercial ships from traversing the passage without the assistance of icebreakers.

In 2014 the MV Nunavik, was the first cargo ship to sail through the Northwest Passage without an escort from icebreakers. Although the winter challenges will remain, the processes of climate change may now be opening the once-icebound passage to more regular shipping and permitting the summer shipping season in Arctic Canada to be extended. The number of transits increased from 4 per year in the 1980s to 20–30 per year in 2009–2013, according to the State of the Environment, 2015. The National Snow and Ice Data Center registered yearly record low levels, but the Canadian Government recent researches cast doubt on whether its regular use for commercial shipping will be happening any time soon. The studies finds that even with declining ice overall, the waters of the Northwest Passage are still full of thick and persistent ice, which is detracting the predictability of navigation. However, the navigation for smaller boats, yachts, and tourist cruises is evaluated differently, it is expected to increase exponentially. Recent studies about this topic are: Whitney Lackenbauer and Adam Lajeunesse. On Uncertain Ice: The Future of Arctic Shipping and the Northwest Passage, Policy Paper, December 2014. Prepared for the Canadian Defence & Foreign Affairs Institute and C. Haas, and S. E. L. Howell. “Ice thickness in the Northwest Passage”. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42 (2015): 7673–7680, doi:10.1002/2015GL065704. In other words: It is very difficult to make any previsions for several reasons: the collection of data was only started recently; weather conditions are very variable; and Canadian Government doesn’t encourage the passage because they don’t have the means to patrol and control the sea.

This exhibition approaches the Northwest Passage from several different perspectives: the epic voyages in search of the mythical passage; the topography of the territory and how states have asserted sovereignty over such Arctic regions; the debates fueled by the discovery of oil in the Alaska North Slope area in 1968; and the effects of climate change and ice melt. Combining text and multimedia components, the exhibition also explores questions about the relationship between tradition, culture, environment, and economic benefit.

Climate defines the Arctic and the people who live within it. Compared to other parts of the Earth, it is especially deeply affected by the changes resulting from human and natural causes.

Climate defines the Arctic and the people who live within it. Compared to other parts of the Earth, it is especially deeply affected by the changes resulting from human and natural causes. Westerners’ approach to climate change in this remote part of the world oscillates between paranoid apprehension and boundless expectations of the possibilities and resources.

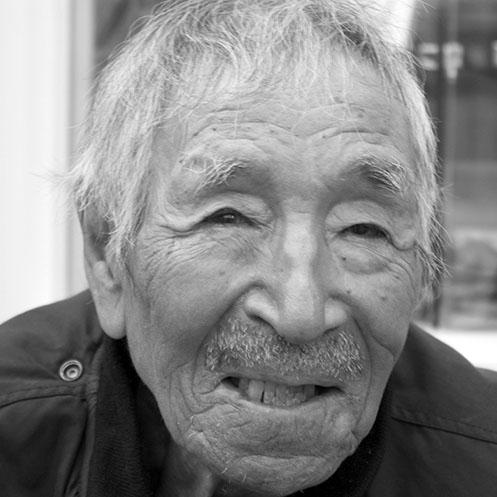

Local Inuit and Natives react in a different manner. Their experiences date back several millennia and move between temporal and spatial boundaries. For those who must survive this harsh climate, constant observation of the weather continues to be an important part of daily life. As a result, Inuit have much to contribute to our awareness of climate. What can we understand from the different approaches? Is the Passage today, as it was in past, a place where the two different cultures and “knowledge systems” can meet and interact?

Is the Passage today, as it was in past, a place where the two different cultures and “knowledge systems” can meet and interact?

These questions were not fully clear when I started my research, but rather evolved gradually as I interacted with Inuit residents. The exhibition benefits from the results of a voyage in the Arctic and the opportunity to meet with the elders of the Community of Cambridge Bay, Nunavut; it was supported by the Kitikmeot Heritage Society and the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. These encounters, parts of which are presented in the short videos included in this exhibition, showed me how much my Western perspective influenced my views on the environmental experience.

On this journey the Passage becomes a sort of key, a metaphor of the meeting between the Western thirst for understanding, mapping, owning and ruling, and the Native spiritual, adapting, holistic, and integrated way of reacting to changes and to the unknown.

Inuit voices led me to ask some very different questions concerning the way we think about and respond to our climatic reality, and how, taken together, Western scientific knowledge and Inuit knowledge could provide complementary ways of knowing. On this journey the Passage becomes a sort of key, a metaphor of the meeting between the Western thirst for understanding, mapping, owning and ruling, and the Native spiritual, adapting, holistic, and integrated way of reacting to changes and to the unknown.

Observing Change, Feeling Nature

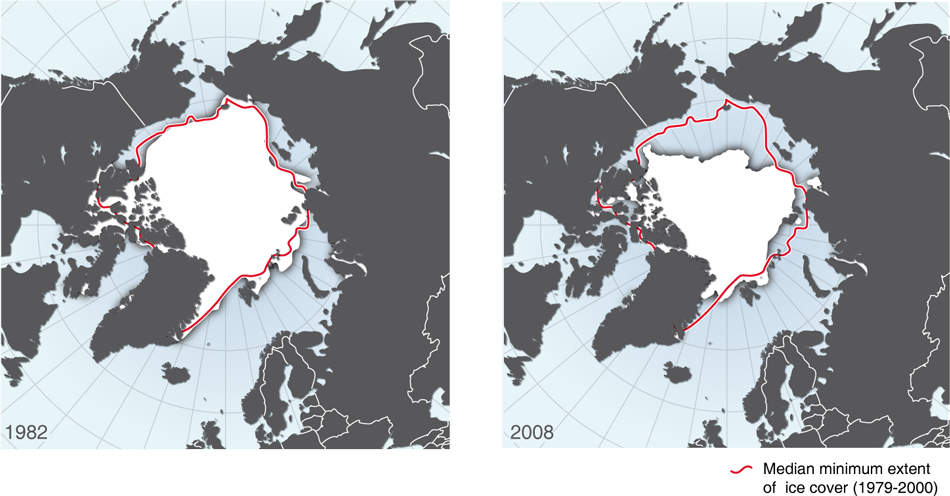

Global warming and climate change refer to an increase in average global temperatures. Whatever the causes—natural events, human activities, greenhouse gases—and long-term forecasts and predictions, we know that rising global temperatures will speed up the melting of glaciers and ice caps, and cause early ice thaw on rivers and lakes. Shrinking Arctic sea ice is one of the most visible indicators of this change in climate, and year-round scientific analysis of ice conditions and permafrost temperatures confirm such changes.

Source: Hugo Ahlenius, UNEP/GRID-Arendal

Publisher: International Polar Year (IPY) educational posters, 2008

Click here to view source.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

No. 2. Arctic sea ice minimum extent in September 1982 and 2008. The red line indicates the median minimum extent of the ice cover for the period 1979–2000. This figure compares the Arctic sea ice extent in September for the year 1982 (the record maximum since 1979) and 2008. The ice extent was 7.5 million square kilometers in 1982, only 5.6 million square kilometers in 2005 and down to 4.3 million square kilometers in 2007. As has been observed in other recent years, the retreat of the ice cover was particularly pronounced along the Eurasian coast. Indeed, the retreat was so pronounced that at the end of the summers of 2005 and 2007 the Northern Sea Route across the top of Eurasia was completely ice-free. Source: Hugo Ahlenius, UNEP/GRID-Arendal.

Melting ice caps will lead to larger ice-free water areas for longer periods of time and an Arctic Ocean that is open for business at least through the summer months. This in turn will increase seasonal shipping and provoke territorial disputes among the powers that lay claim to sovereignty for the exploitation of the riches in the subsoil. Shorter ice periods will open up historically closed shipping routes, including the Northwest Passage.

In Inuit culture, changing weather is interpreted in connection with Sila mythology. Sila is an important aspect of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, an Inuktitut term that translates as “Inuit traditional knowledge,” but is very difficult to define. It encompasses all aspects of traditional Inuit culture, including values, world view, language, social organization, knowledge, life skills, perceptions, and expectations. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is a complex concept connected to the “Inuit way of doing things,” and includes the past, present, and future knowledge of the Inuit society.

Scientists refer to Sila as weather, while ethnographers consider it a mystic power or a godlike Supreme Being. For Inuit elders the term includes more than this: it is the forces that push or pull a person through life, or simply wisdom. Sila is the primary component of everything that exists, the breath of life as well as the motion for any movement or change. It has the power to control everything that goes on in one’s life and is also the substance of which souls are made. Sila is a deity of the sky, the wind, and weather. Sila is not a personification of human beings, but rather the person is owned by Sila: humanity is the personification of Sila.

No. 3. Sila. The video defines the meaning of “Sila” in Inuit culture. Video by Elena Baldassarri. August 2013. Interviews with Timothy Leduc, Jimmy Maniyogina, Ana Nahogaloak. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In their rich history of living as hunters, Inuit have developed intimate cultural ties to life and death. They hold a deep understanding that without the death of the living, there is no life, so the dead are the foundation upon which life exists: death gives rise to life. Breathing is what distinguishes living creatures from dead ones. This life force can neither be created nor destroyed, because it recycles itself continually: when any creature—human or beast—perishes, its Sila (“breath” or “life”) leaves that particular body, dissipates into the larger whole, or finds its way into a new form.

Sila, with all its different meanings, refers to life, nature, observation of the environment, and adaption. Sila permeates and surrounds Inuit communities as a constantly-moving spiritual force. Understanding Sila, and allowing it to own our selves, could help to guide human actions.

Another Inuit concept related to Sila is the Silarjuaq, the universe, which is in constant flux and change, a condition suggestive of the human mind. Sila is sentient because it modifies nature and spirit. Thanks to the transformation it obligates each being to be responsible for the other and enables us to contextualize ourselves within the environment—that is, to be fully part of the environment.

Talking with Inuit and listening to their stories raises two pivotal concepts likely to interact with changes in nature: observation, and adaptation, both of which pass through Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. As Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is an accumulated and evolving body of knowledge, conciliating intergenerational survival skills, practices, and experiences, it is grounded on an acute awareness of dynamic interactions between humans, land, and resources.

Even if Western scientific observations are based on instrumental documentation and on observations over a specific period of time, Inuit traditional knowledge represents an understanding of change. Together, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and Western scientific knowledge provide complementary ways of knowing.

Even if Western scientific observations are based on instrumental documentation and on observations over a specific period of time, Inuit traditional knowledge represents an understanding of change. Together, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and Western scientific knowledge provide complementary ways of knowing.

Traditional knowledge helps to preserve experiences and indigenous history in the collective memory, but also the dynamics, and the manners in which they have faced major changes in the past. Indigenous resilience has always been considered to be connected with their degree of vulnerability: the more flexible the Inuit were, the higher a chance they had of surviving. Today, their resilience is essential to determining how they will respond to the challenges posed by climate change. Even in the face of major changes, indigenous communities will attempt to adapt within the constraints of the cultural, economic, political, international, and local circumstances that shape their lives. As with all adaptations, the measures developed in the Arctic in response to change will protect some aspects of society at the expense of others.

Nature has the last word, and humanity’s obligation is to reflect that wisdom.

—Jaypeetee Arnakak

The history of the Northwest Passage is essential to understanding this resilience. Historically, the Passage was thought to be the way through which Westerners approached, bringing with them not only tools but also new creeds, spirituality, and morality, thus changing Inuits’ connection with nature. This encounter, or clash, deeply transformed the Inuit way of life and in some cases nearly destroyed their traditional knowledge. However, the Inuits’ flexibility, and their accumulation of specialist and generalist knowledge, equipped them with resilience. Such adaptations enhanced their options and were—and still are—important for survival. If we do not expand scientific data with historical Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, there will continue to be significant deficiencies in our understanding of Arctic climate change, because, as the Inuit philosopher Jaypeetee Arnakak has stated: “Nature has the last word, and humanity’s obligation is to reflect that wisdom.”

No. 4. Adaptation and tradition. Video covering the meaning of climate change and adaption in both southern and Native culture. Interviewers relate, from their different points of view, to the issue of tradition and knowledge, and how it can be used to build resilience to the adverse impacts of climate change. Video by Elena Baldassarri. August 2013. Interviews with Joe and Susie Koaha, Timothy Leduc, Jimmy Maniyogina, Ana Nahogaloak, Brenda Sitatak, and Mary Avalak. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society which provided full funding to complete the study and offered the possibility to organize a challenging travel. Similarly, I would like to extend great thanks to the Environment & Society Portal team who generously offered time, assistance, commitment, and encouragement. This research looks very different because of their input, help and expert knowledge.

This project is the result of the author’s research and studies, and in particular of an excursion to the Arctic Circle in summer 2013 that took the author across the Atlantic and to Nunavut, specifically to Cambridge Bay, on a twenty-first century journey in search of the Northwest Passage. Meeting scholars, authorities, and local people helped the author to understand the complexity and richness of this issue: everyone has their own point of view and experience, with each perspective further enhancing the project.

Many thanks to all those interviewees for sharing their stories, opinions, and feelings.

This work was produced by Elena Baldassarri with StoryMapJS and OpenStreetMap.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

No. 50. Map showing the journey taken by the author. Click here to open this storymap in a new tab.

Cambridge Bay

Many thanks to the Nunavut Research Institute (NRI), who granted the Scientific Research License for the project and so made it possible to meet and talk with elders in Cambridge Bay. The Community of Cambridge Bay warmly welcomed us, and the Kitikmeot Heritage Society offered its space. The hamlet was named by Hudson’s Bay Company in 1839 and is located on the shore of the Northwest Passage. The HBC opened a post in 1927 and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrived in 1926. Until the 1950s few Inuit lived here; it was not until the construction of a LORAN Navigational Beacon in 1947 and of a Dew Line site in 1955 that the community began to expand.

I cannot express enough thanks to Renee Aldona Krukas of the Kitikmeot Heritage Society for her continued support and help in Cambridge Bay. My voyage could not have been accomplished without her.

A special thanks to Ana Shorter for providing her voice for the audio recording, and for her suggestions for the videos.

Finally, my deepest gratitude to Enrico Mariotti, who shared with me this trip, the never-ending flights, and the snow and summer blizzards, and whose presence and sensitivity are reflected in the pictures included in the exhibition.

Dr. Kathrin Keil

Europe Director—The Arctic Institute Center for Circumpolar Security Studies

Dr. Kathrin Keil

Europe Director—The Arctic Institute Center for Circumpolar Security Studies

Kathrin Keil wrote her PhD Dissertation at the Berlin Graduate School for Transnational Studies (BTS) at the Freie Universität Berlin on the international politics of the Arctic, with a focus on international regimes and institutions in the areas of energy, shipping and fishing. She further has a Bachelor of Arts in International Relations from the Technische Universität Dresden and a Master of Science in European Affairs from Lunds Universitet in Sweden. Her fascination with the Arctic began during an internship at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP Berlin) in 2009 and continued during her doctoral research.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Dr. James Manicom

Research Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)

Dr. James Manicom

Research Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)

Research Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) contributing to the development of the Global Security Program. Previously, he held fellowships at the Ocean Policy Research Foundation in Tokyo and the Balsillie School of International Affairs. His current research explores Arctic governance, East Asian security and China’s role in ocean governance.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Prof. Franklyn Griffiths

Department of Political Science, Toronto University.

Prof. Franklyn Griffiths

Department of Political Science, Toronto University.

Prof. Franklyn Griffiths

Professor Emeritus, Department of Political Science, Toronto University. Research interests include international politics, particularly international security affairs; the politics and foreign policy of Russia and the USSR; and Arctic international relations. Publications include: Skilling, H. Gordon, and Franklyn Griffiths. Interest groups in Soviet politics. Princeton, N.J.: [Published for the Centre for Russian and East European Studies, University of Toronto by] Princeton University Press, 1971; Griffiths, Franklyn, and J. C. Polanyi. The Dangers of nuclear war: a Pugwash symposium. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1979; Griffiths, Franklyn. Arctic alternatives: civility or militarism in the circumpolar North. Toronto, Ont., Canada: Science for Peace, 1992; Griffiths, Franklyn. Strong and free: Canada and the new sovereignty. Toronto: Stoddart, 1996.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Prof. Timothy Leduc

Assistant Professor, York University

Prof. Timothy Leduc

Assistant Professor, York University

Prof. Timothy Leduc

Assistant Professor, York University. Before graduating with a PhD in Environmental Studies, CHN Contributor, Timothy Leduc, completed a masters degree in social work, and worked for a number of years in northern indigenous communities and on anti-violence issues. His doctoral research built on these experiences by bringing Inuit ecological and cultural views of northern warming into dialogue with Western climate research as a means for interculturally assessing the current politics of inaction. The resulting book, Climate, Culture, Change: Inuit and Western Dialogues with a Warming North, was shortlisted for the 2012 Canada Prize, and related articles have been published in journals like Tikkun Magazine and Worldviews.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Dr. Adam Lajeunesse

Research Assistant, Department of History, University of Calgary

Dr. Adam Lajeunesse

Research Assistant, Department of History, University of Calgary

Dr. Adam Lajeunesse

Research Assistant, Department of History, University of Calgary. He received his Doctorate in History at the University of Calgary in December 2012. His research has focused on the evolution of Canadian government policy over the Arctic waters and on Canadian-American defence and law of the sea relations in that area. He has also written on a number of other subjects, including contemporary Arctic sovereignty and security concerns, shipping prospects, hydrocarbon development and international relations.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Diego Creimer

Media and Public Relations Office

Diego Creimer

Media and Public Relations Office

Diego Creimer

Media and Public Relations Office. Greenpeace Canada. He is the manager for Greenpeace Arctic campaign Save the Arctic.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

John Higginbotham

Senior Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)

John Higginbotham

Senior Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)

John Higginbotham

Senior Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI). Expert on international economic relations, maritime, air, road, and rail transportation systems and systems of governance, he leads CIGI’s global security and politics research project on the Arctic. He is also a senior distinguished fellow at Carleton University, where has he been working on the Arctic, China, and the United States, as well as a transport studies initiative drawing on the strengths of Carleton’s faculties of Business, Public Administration, and Engineering. He has worked for the Government of Canada and served as assistant deputy minister in three departments, including Transport Canada. He has served abroad in senior positions in Washington for six years, Hong Kong for five years, and in Beijing on two occasions, as a trade commissioner and political counselor.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

How to cite

Baldassarri, Elena. “The Northwest Passage: Myth, Environment, and Resources.” Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2017, no. 1. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/6254.

ISSN 2198-7696 Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions

2017 Elena Baldassarri

2017 Elena Baldassarri

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter